Every year that I teach the American Revolution, I often ponder new questions related to the event. One question that I’ve asked myself this year is: Could have cooler heads prevailed in the lead up to the American Revolution? The primary, foundational disagreement between the American colonists and the British government was the simple question: “Did the British Parliament have the right to tax the colonists?” The colonists were so steadfast with an emphatic “NO” that they were willing to protest, boycott, destroy property and risk going to war. The British responded with an empathic “YES”. They were so steadfast that they were willing to tighten control over the colonies, send British troops to enforce its laws, close Boston’s port for trade, enact martial law in Massachusetts, and alter the justice system of the colonies. The British were so committed to their power to tax the colonists that they were willing to go to resort to war.

There is no doubt that the colonists drew a line in the sand against British infringements on their rights as Englishmen. There is also no doubt that the British officials were quite stubborn with their unwillingness to listen and work with the American colonists. The British had a reputation to defend and were unwilling to give in to colonial demands. There was a sense of arrogance in their responses to the colonists throughout the controversies that occured between 1763- 1775. Had the British been more willing to negotiate, was it possible that war could have been avoided? Or was an independence movement in the colonies inevitable? I explore these questions later in the blog post, but first, I’ll highlight the chain of events and laws that continued to build tensions between the two sides.

Tensions Emerge at the Conclusion of the French and Indian War

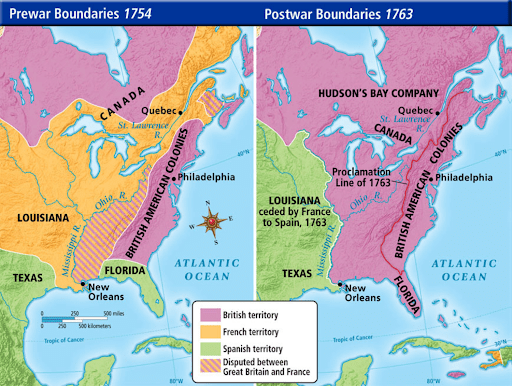

The French and Indian War (The American Theater of the global, Seven Years’ War) started in 1754 and ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. It was a conflict that emerged between the growing French Empire (along with Native allies) and the British Empire around the Ohio Country, the Great Lakes, and in Canada. The British emerged victorious and kicked the French out of their North American holdings. At the conclusion of the war, the British Empire in North America stretched from the east coast to the Mississippi River. In its aftermath, the British racked up a debt nearly double what it was before the conflict.

The British passed the Proclamation of 1763 to ban new colonial settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains. This was an effort to limit conflicts between the American colonists and Native Americans. The British sent about 10,000 British troops to the frontier to regulate the ban and limit any future tensions with the French and Natives. The American colonists saw the British stationed in the colonies as a standing army in a time of peace, which was unacceptable according to 18th century norms.. The standing army only added to Britain’s debt.

The British government believed that the American colonists should pay for their own protection and passed a series of laws that would extend the tax burden onto the colonists. Along with the taxes were a number of events that further led to tensions between the British government and the American colonists. Let’s take a walk through the timeline below to highlight the growing friction between the two sides:

1763- The Treaty of Paris (Ends the French and Indian War)

1763- Passage of the Proclamation of 1763- highlighted above.

1764- The Sugar Act

The British passed this law to address illegal smuggling by the colonists. The Navigation Acts, which had been passed throughout the colonial period, allowed the colonists to only trade with England. The colonists freqently smuggled goods into the colonies including tea, molasses, sugar and other items. The Sugar Act sought to do two things- split the tax on foreign sugar/ molasses in half, (with the hopes that the colonists would pay the lower tax) and strengthen the enforcement of the law, allowing prosecutors to try smuggling cases in vice-admiralty courts with only a British judge and not a jury. While the colonists were opposed to the act, there was not widespread anger or oppostion (like we’d see with the Stamp Act). The colonists understood that this act was written to regulate trade, not necessarily to raise revenue for the Empire.

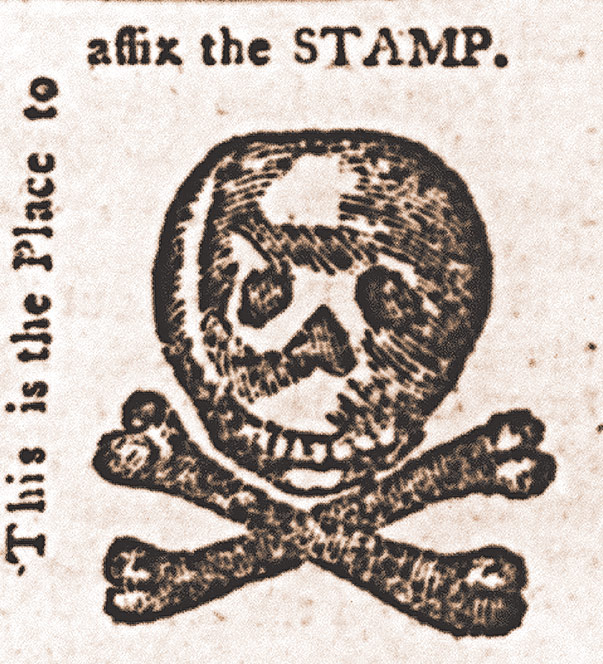

1765- The Stamp Act

This law led to fierce, widespread anger throughout the colonies. The Stamp Act required all paper products: legal documents, newspapers, licenses, pamphelts, almanacs, playing cards, and even dice to be taxed. This was a direct tax that affected all colonists. Never before in colonial history had the British Parliament taxed the colonies in such a manner. The colonies had only been taxed by their colonial legislatures. The central argument from the colonists was “No Taxation Without Representation.” The colonists argued that because they were not represented in the British Parliament, that body did not have the right to take their property (in the form of a tax). This was an age old belief in England and the colonists wanted to be treated the same as people in the motherland.

The British response was that the English colonists were virtually represented by the British Parliament. Most citizens in the England could not elect their representatives because of property requirements for voting. Just as those individuals were represented by Parliament, so too were the colonists. The American colonists did not buy this argument and continued to state that the taxes were unconstitutional. To them, only the colonial legislatures could tax the colonists because their local government was where they were represented.

The rage of the colonists led to protests, boycots, riots, the tar and feathering of tax collectors, and the destruction of private property. These actions worked because the following year, the British Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, pressured by British merchants who were feeling the pinch of the colonial boycotts. However, the British also passed the Declaratory Act, stating that the British Parliament had the right to make laws “to bind the colonies and people of America… in all cases whatsoever.”

1765- The Quartering Act

The Colonies had to provide inns, alehouses, barns and other buildings to house British soldiers at the expense of the colonies. This was seen as another tax because the colonial governments had to foot the bill.

1767- The Townshend Acts

In response to the repeal of the Stamp Act, the British passed a series of acts referred to as the Townshend Acts (after British offical, Thomas Townshend). The acts included indirect taxes on goods arriving into the colonies from Great Britain, including glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea. Widespread protests and boycotts followed with the same argument as the Stamp Act. Even though this was an indirect tax, the colonists argued that it was still a tax to raise revenue for the British crown, and was therefore, unconstitutional. In the next few years, the Townshend Acts were repealed, except the tax on tea. The primary reason that British Prime Minister, Lord North wanted to keep the tax on tea, was to prove to the colonists that the British Parliament had a right to tax the colonists.

1768- The Liberty Affair

The ship called the Liberty belonging to known smuggler and wealthy merchant, John Hancock, was seized by British officials. Hancock was accused of smuggling wine from Madeira without paying customs duties. The incident led to riots in Boston, encouraging the British to send 2,000 troops to the city.

1770- The Boston Massacre

On the evening of March 5th, a crowd gathered outside the Boston Customs House and began threatening a British soldier, who called for backup. After seven more soldiers arrived, the scene continued to escalate as the mob grew larger. Members of the mob even dared the British soldiers to shoot. The crowd threw snow, ice and other projectiles at the soldiers, until one British officer fell to the ground and then fired his gun. Other British officers fired as well, killing 5 and wounding six in what the colonists called “The Bloody Massacre”. An engraving of the event (an early form of propoganda) by Paul Revere published in the newspapers increased the anger that the colonists felt for the British. As a result of the soldiers’ trial, six were cleared of any wrongdoing while two were convicted of manslaughter and punished with a branding on the thumb. The soldiers were defended by John Adams, who wanted to prove to the British that the American colonists believed in the right to a fair trial.

1772- Gaspee Affair

A British ship called the HMS Gaspee ran aground as it was attempting to enforce the Navigation Acts. A group of colonists attacked, boarded, and set the ship aflame leading to anger from the British government. King George III called on the perpetrators to be caught and brought to Great Britain to stand trial. While the perpetrators were never actually caught, the idea of bringing colonists to Britain for trial only added to the anger and fear amongst the colonists.

1773- The Tea Act

Throughout the colonial period, the colonists were frequently smuggling cheap tea into the colonies from the Dutch. This, of course, was in direct violation of the Navigation Acts. In response, the British passed the Tea Act which allowed the British East India Company (which had tons of unsold tea and was nearly bankrupt) to sell their tea directly to the colonists. Prior to the Tea Act, the British East India Co. sold its tea at the London Tea Auction to tea merchants. The tea merchants then sold it to colonial tea merchants, who then sold it to the colonists. This process made British tea more expensive than smuggled Dutch tea.

As a result of the Tea Act, the British East India Co. could now sell their tea directly to the colonists and take out the middlemen, the tea merchants. Even with the the additional tax on tea (which was the holdover from the Townshend Acts), Prime Minister Lord North was hoping that the colonists would simply purchase the cheaper British tea. Instead, the colonists reacted violently. The colonists knew that this was a sneaky way for the British to still force the colonists to pay the tax on tea.

As the tea ships landed throughout the colonies, the colonists refused to allow the tea to be unloaded in the colonies. Through threats of violence by the colonists, the British officials were unable to unload the tea, and brought the tea ships back to England. An example of this is what is referred to as the “Philadelphia Tea Party”. The only British official who refused to give in to the colonists, was Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson. He would not allow for the tea ships to be brought to England, and therefore, three tea ships sat in the Boston Harbor.

1773- The Boston Tea Party

Boston colonists, likely led by the Sons of Liberty and many disguised as Native Americans, boarded the three ships and dumped all of the tea into the Boston Harbor. In today’s U.S. dollars, the British East India Company lost about $1.7 million worth of tea.

1774- The Intolerable Acts

King George III was enraged when he heard of the destruction of the tea. Even members of Parliament who had been sympathetic to the colonists before, had completely turned on them. Lord North wanted to punish Massachusetts, and Parliament passed a series of laws that the colonists called the Intolerable Acts (The Coercive Acts from the British perspective). The British shut down Boston’s port until the tea was paid for. This would stop all exports and imports to and from the port of Boston.

The Massachusetts government was altered. Thomas Gage, the British Commander in Chief of armed forces, was the Masachusetts governor, and voting rights were taken away from the colonists. Town meetings were limited to no more than once a year.

British officials accused of a crime in Massachusetts would have their trial in Great Britain. George Washington referred to this law as the “Murder Act” because now British soldiers could get away with murder by having their trial in a sympathetic British court.

Finally, a stricter Quartering Act was passed, ensuring that the British were housed in vacant private homes and other public buildings.

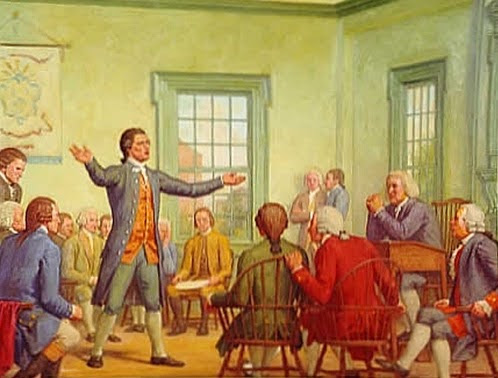

1774- The First Continental Congress

The colonies were united in their outrage over the Intolerable Acts. They met in Philadelphia at the First Continental Congress to decide their next steps. They wrote a petition to the king, asking for a repeal of the Intolerable Acts, and a return to the prior harmony that the colonists and the mother country had previously shared. The petition was ignored. The Congress agreed to boycott British goods until the Intolerable Acts were repealed. The Congress also agreed that each colony should set up and train its own militia.

April 1775- Lexington and Concord

With heigtened tensions, the British learned that the colonists were stockpiling weapons and gunpowder in Concord, MA. The British planned to capture Sam Adams and John Hancock in Lexington and seize the arsenal in Concord. The famous “shot heard round the world” came on the village green in Lexington, and the Revolutionary War began.

As we can see with the timeline, tensions continued to escalate from the end of the French and Indian War. But could they have been avoided? Could perpetual peace have been possible without the shedding of blood and a war that would last 8 years?

Was Independence Inevitable Or Was Reconciliation Possible?

Let’s take a look at the two sides: The colonists and the British government.

The Colonists’ Viewpoints

The colonists, as mentioned above, drew a line in the sand against British taxes. They were not willing to budge on the issue, especially ardent Patriots. But the long-term causes of independence goes back further- well before 1763. In the late 1600s and for most of the 1700s, the British approach to the American colonies can be described with the phrase, “Salutary Neglect”. The British generally left the colonies alone and did not strictly enforce their laws for the continued devotion of the colonies. Throughout this time period, there was relative peace between the two sides. However, the colonists were displeased with the Navigation Acts, which required the colonists to only trade with the British. While the colonies were growing, they were increasingly feeling a sense of independence. They elected leaders to their own colonial governments, and they felt they could fend for themselves and run their own affairs through brilliant and tenacious leaders, who would become the Founding Fathers. They were an ocean away from Mother England, and were capable of governing themselves.

Therefore, when the British began enforcing laws more strictly and passing new direct tax laws, the colonists were understandably outraged. The colonists truly believed that the British government was acting in a way that was unprecendented. It seems that independence was inevitable, and the movement towards independence needed a spark of anger. This outrage came from British taxes.

What about from the British side?

Could the British have made peace with the colonists and avoided independence? To me, they could have done a much better job in their approach to the concerns of the colonists. But if they would have been more benevolent towards the colonies in the 1760s and 1770s, they may have been simply delaying an eventual indpendence movement.

The British government after 1763 was quite headstrong in their belief of taxing the colonies. The British were not willing to negotiate with the colonists during the many controversies between 1765- 1774. The chasm between the colonists and the British grew wider and wider. It’s clear that the British looked down upon their American countrymen. This can be seen in the ways that the British military viewed American military leaders, such as George Washington, during the French and Indian War. An American could not work his way up to become a British general. If you view Mother England and her American colonies as a parent-child relationship, Mother England was in the driver seat as to how the relationship was to develop.

There likely was a belief amongst the British leadership that if they continued to tighten controls over the American colonies, that perhaps the colonists would rebel. If that were to happen, the British would easily crush the rebellion, and maybe tighten controls over the colonists even more. The Americans had no navy. Their only military forces were inexperienced colonial militias. To the British, there would be no way that the Americans could defeat the mighty British army and navy, if they even dared to try.

When the colonists began to protest against the Stamp Act, it may have caught the British by surprise. At the conclusion of the Stamp Act riots, it appears that the British had the idea that they really needed to prove to the colonists who was in charge.

What if the British had more accommodating leaders?

There could have been peace between the colonists and the British: but only for a time. The Englightenment ideals had spread to the American colonies, and led many to question the very idea of a monarchy. It is quite conceivable that even if the Revolution didn’t break out in the 1770s, there could have been later controversies in later decades that would have fueled an independence movement.

If cooler heads prevailed, and if British leaders were more understanding of the American arguments, I believe there could have been peace between the British and the Americans in the 1770s. However, there was a widespread and growing independence movement in the Americas taking place. The very ideals that Americans were developing in this time period were completely incompatable with the British monarchy. These ideals included political freedom, voting rights, right to a fair trial, and protection from unlawful search and seizure. I believe that independence was inevitable because of these ideals. The British Empire had spread itself too thin at the end of the Seven Years’ War and felt that they needed more money to continue to build their empire. They wanted to force the American colonies into submission in the 1760s and 1770s. This was an approach that ended up backfiring on the British. They took a calculated risk while tightening controls over the colonies, and the result would be American independence and the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionry War in 1783. With that, the British empire lost its vast American colonies in North America.

Reconciliation between the two sides was possible temporarily, but American independence would come sooner or later.

Please let me know your thoughts in the comments or on social media.

Check out related blog posts below: