I am pleased to update readers on an exciting research project currently taking place in New Jersey. The Westfield Historical Society, with the support of the New Jersey Historical Commission, has embarked on a research project aimed at uncovering untold stories of people who lived in Westfield and surrounding towns during the Revolutionary War. The goal is to shed light on both free and enslaved inhabitants of the greater Westfields of Elizabethtown and their roles at the time of the Revolution.

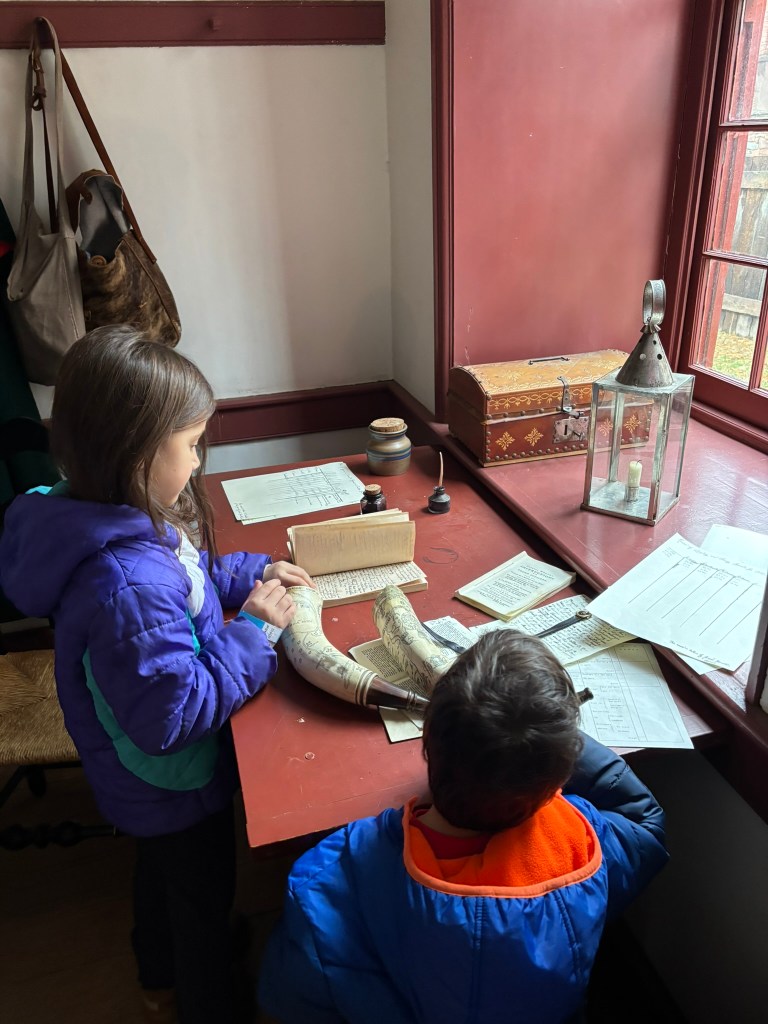

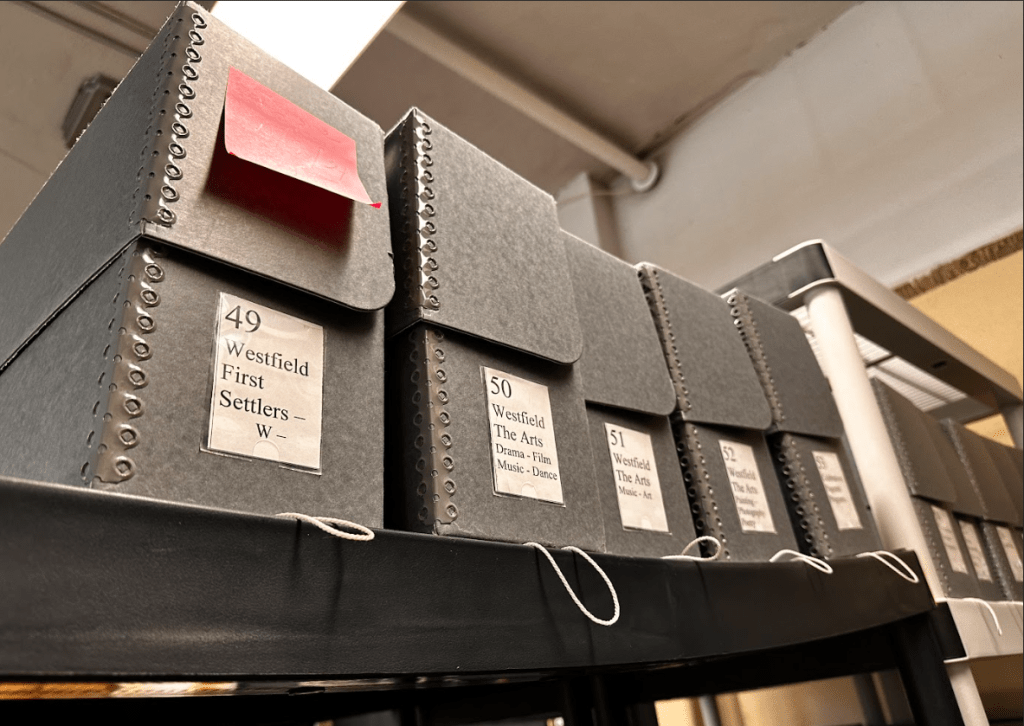

The project, an initiative of Fiscal Year 2025, is seeking to dive deep into historical records from multiple sources including the Westfield Presbyterian Church, the New Jersey State Archives, the New Jersey Historical Society, and other repositories of information. An accomplished team of researchers is exploring local archives, birth certificates, manumission records, letters, family trees, and other vital documents to piece together the personal stories of these individuals and share their legacies with the community.

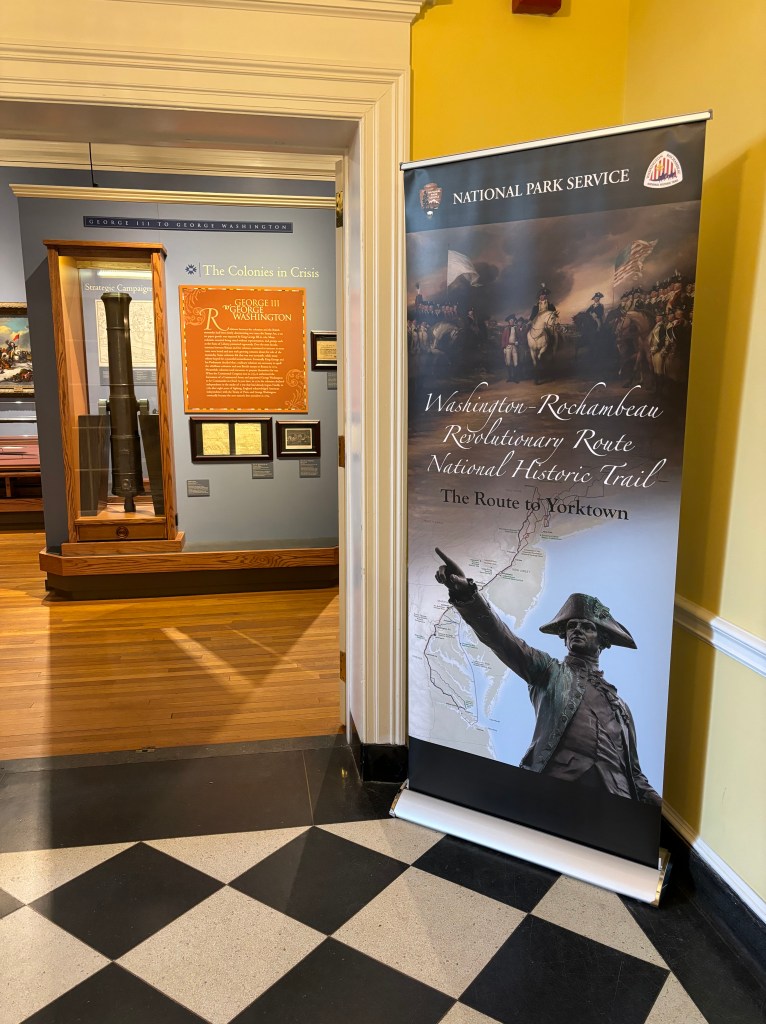

Ongoing research is focusing on the lives of African Americans who lived in the region during the time of the American Revolution. In addition, research is also focusing on the mood of the inhabitants of the region leading up to the Revolution, using evidence from letters exchanged amongst leaders of the area, particularly from committees of correspondence. The researchers, who will be highlighted below, are working closely with Julia Diddell, Chair of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route- New Jersey, as well as Brian Remite, President of the Westfield Historical Society, to comb through enlightening resources.

Julia Diddell led the research project team when we first met in mid-November 2024 to discuss the plan for the upcoming research project, highlighting goals and methods to conduct the research, as well as our long-term plan to present the research to the public.

Another meeting of the team members, led by Julia, took place in late January with updates on new discoveries made, challenges along the way, and future goals. The team was also joined by James Tichemor, who has been doing extensive research at the Westfield Historical Society for this project.

The research project will culminate in a hybrid presentation in June 2025, where the researchers will shed light on their discoveries with the public. The information below provides an update on the progress being made.

A Focus On African American History

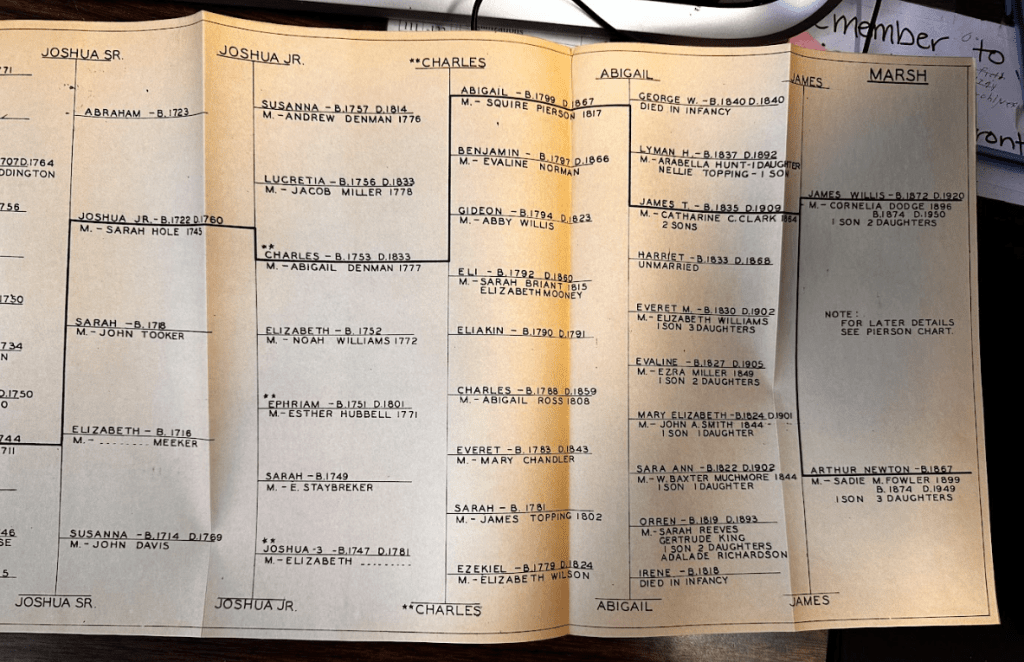

Research is currently being conducted that focuses on the African American community in Westfield and the surrounding towns during the Revolutionary Period. Dr. Susannah Chewning, a Senior Professor of English at the College of Union with a diverse academic background in English Literature and Medieval Studies, is leading this important aspect of the project. Dr. Chewning has been exploring local records, including manumission documents and birth certificates to trace the lives of African Americans in the region. She is working to compile a comprehensive database from her work.

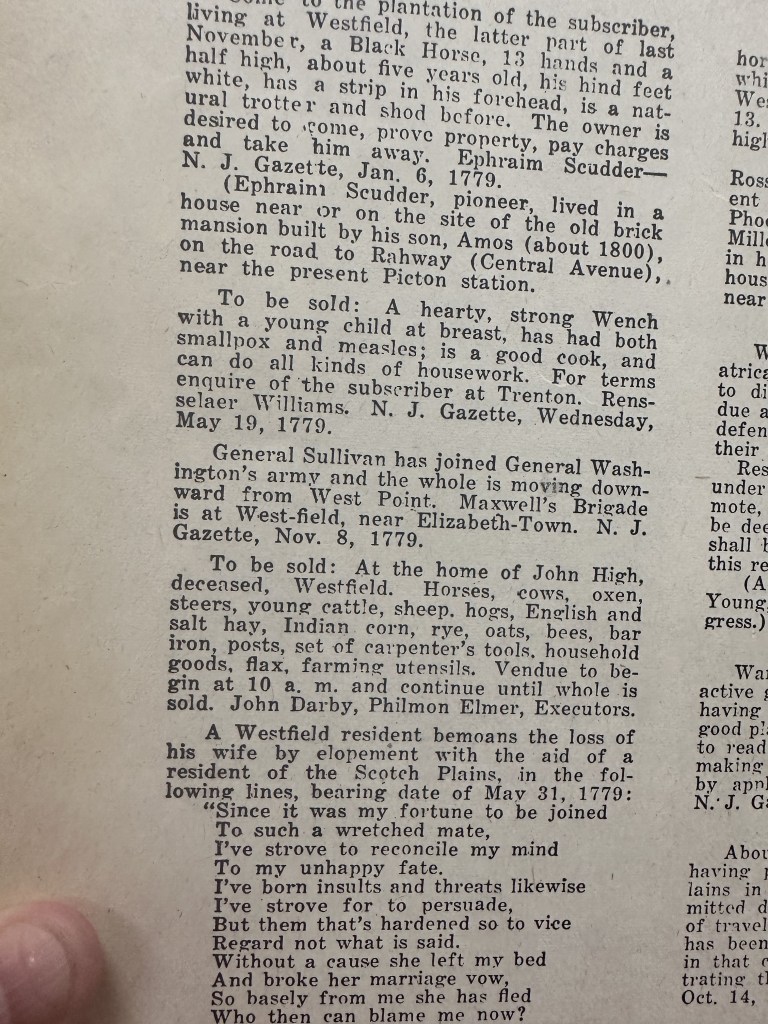

An important part of the research involves investigating the burial sites of African Americans in Westfield. Many individuals, both free and enslaved, were laid to rest in the Old Presbyterian Church Burial Ground. While Dr. Chewning is confident that there are African Americans buried there, only one such grave is currently marked. Research is underway to uncover the other names of these individuals, some of whom were moved when the Fairview Cemetery was established in Westfield in 1868. Dr. Chewning is hoping to identify an African American named Sambo, who was the sexton of the Old Presbyterian Church Burial Grounds during the time of the Revolution. Dr. Chewning has also tracked down evidence of slave sales in the area and plans to find more evidence.

Findings So Far

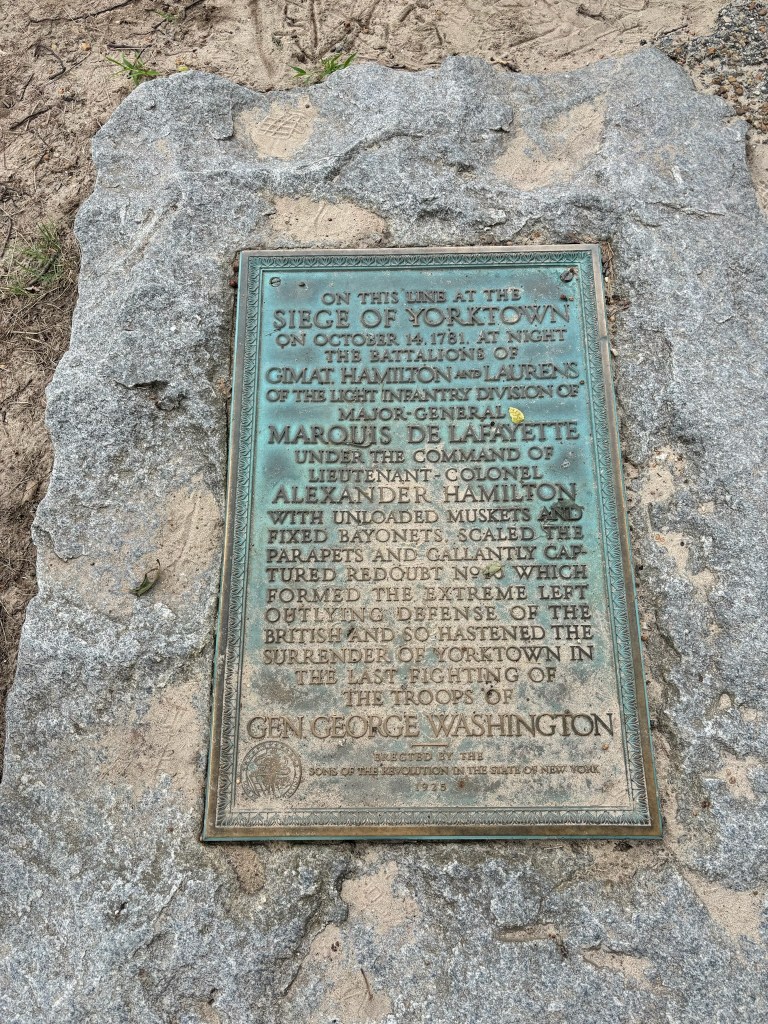

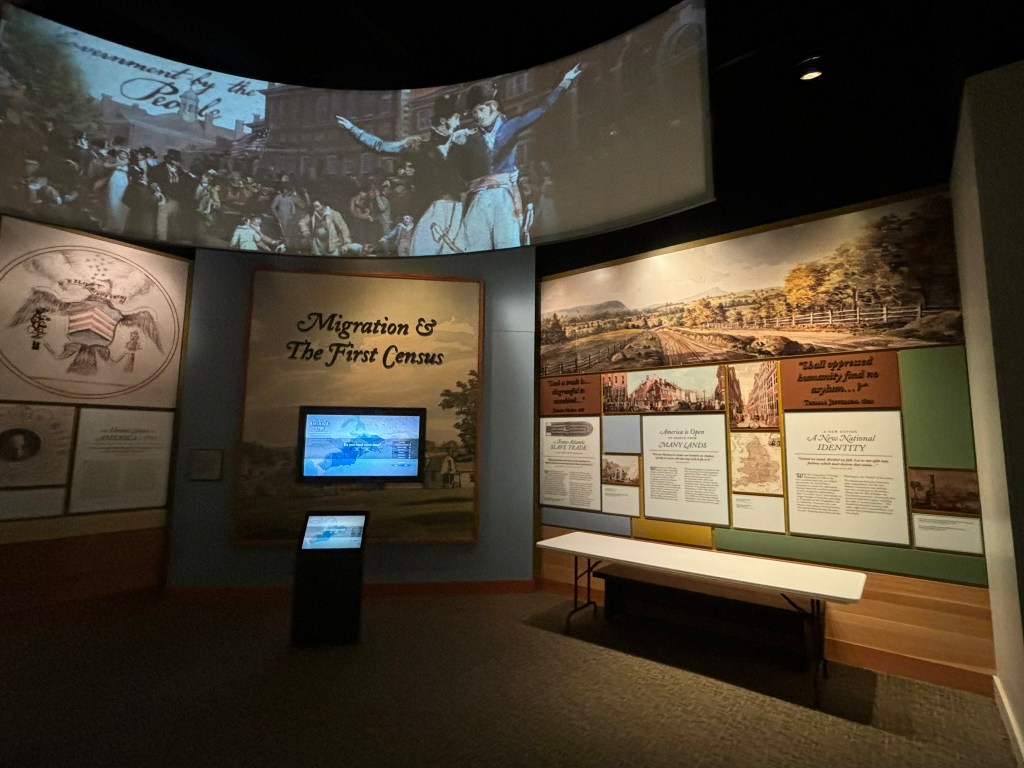

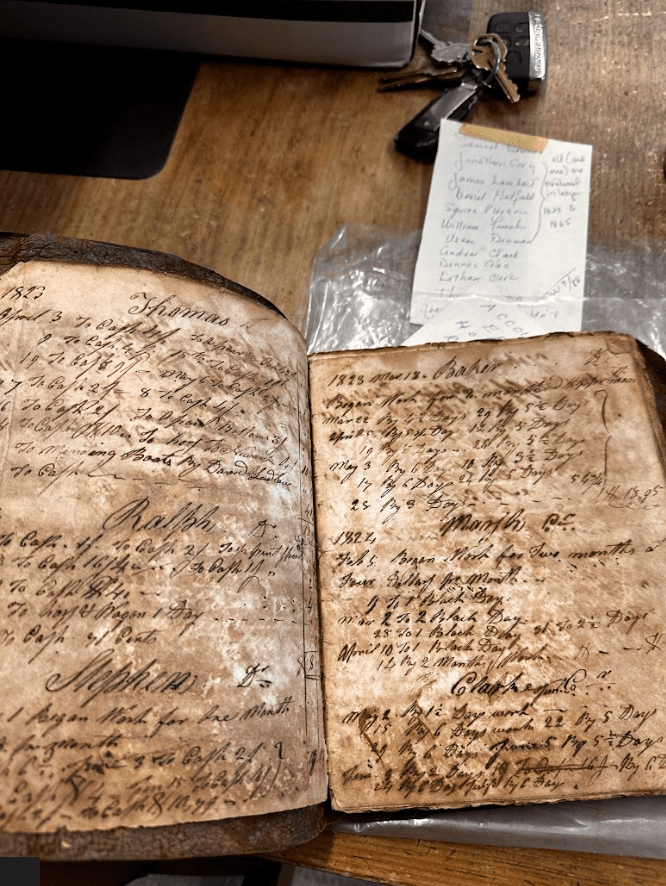

With a growing list of 58 names of African Americans living during the March to Yorktown (1781), Dr. Chewning is dedicated to identifying where these individuals are laid to rest. Her broader research includes 180 (and counting) names of African Americans who lived in Westfield and the surrounding towns between 1702- 1866, the year that slavery finally ended in New Jersey. Dr. Chewning has discovered these individuals through records at the Presbyterian Church, slave sales, runaways, censuses, birth certificates, and manumission records. Recently, Dr. Chewning met with the director at Fairview Cemetery, who provided her with a document highlighting early burials which she has used for her research. Her work at Fairview Cemetery will continue throughout the spring.

In addition to Fairview, Dr. Chewning is continuing her efforts at the Old Burial Grounds where unmarked graves have led to continued efforts to identify those buried there with the support of church and town records. Dr. Chewning has interests in exploring other burial grounds as well, including the Scotch Plains Burial Grounds, where Westfield residents are known to be buried.

Dr. Chewning has compiled a list of families from Westfield who were documented as slaveowners during the time of the 1781 March to Yorktown. Through her research, she has identified not only the names of these families but, in many cases, the names of the individuals they enslaved. This list continues to expand as Dr. Chewning continues her research.

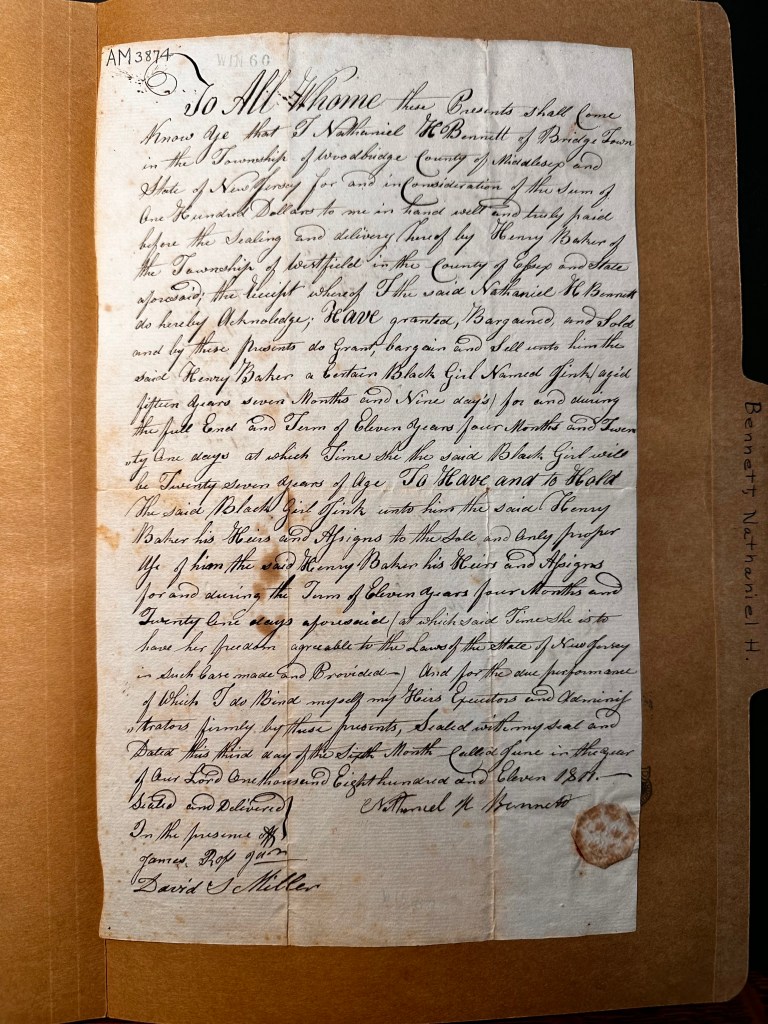

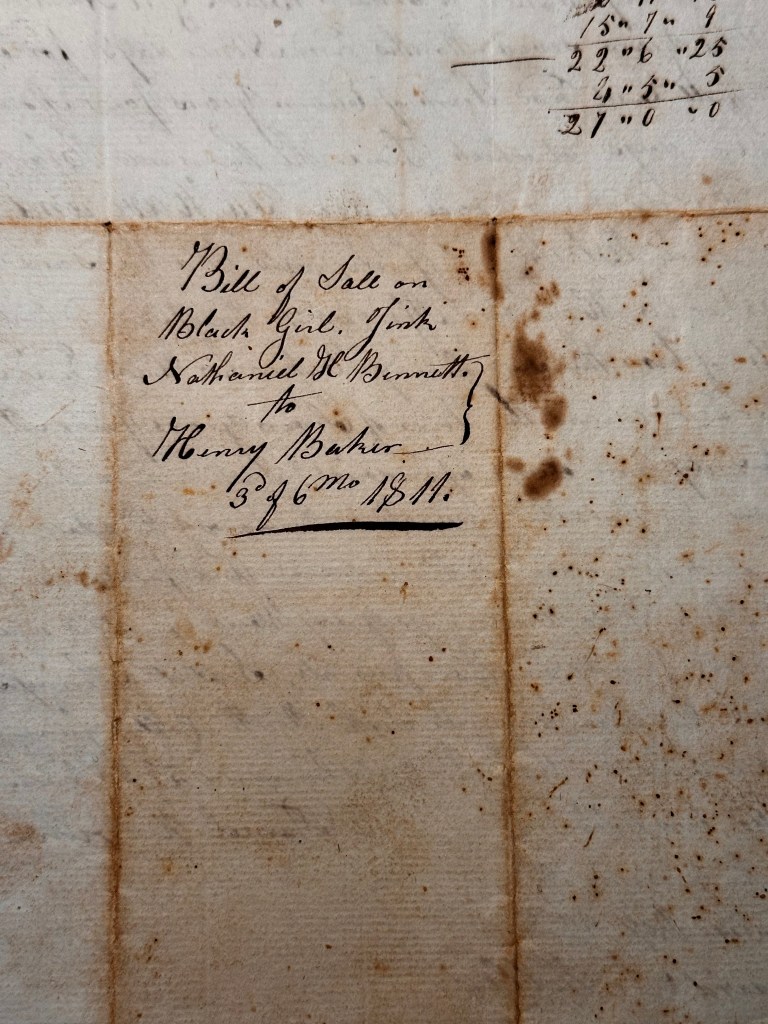

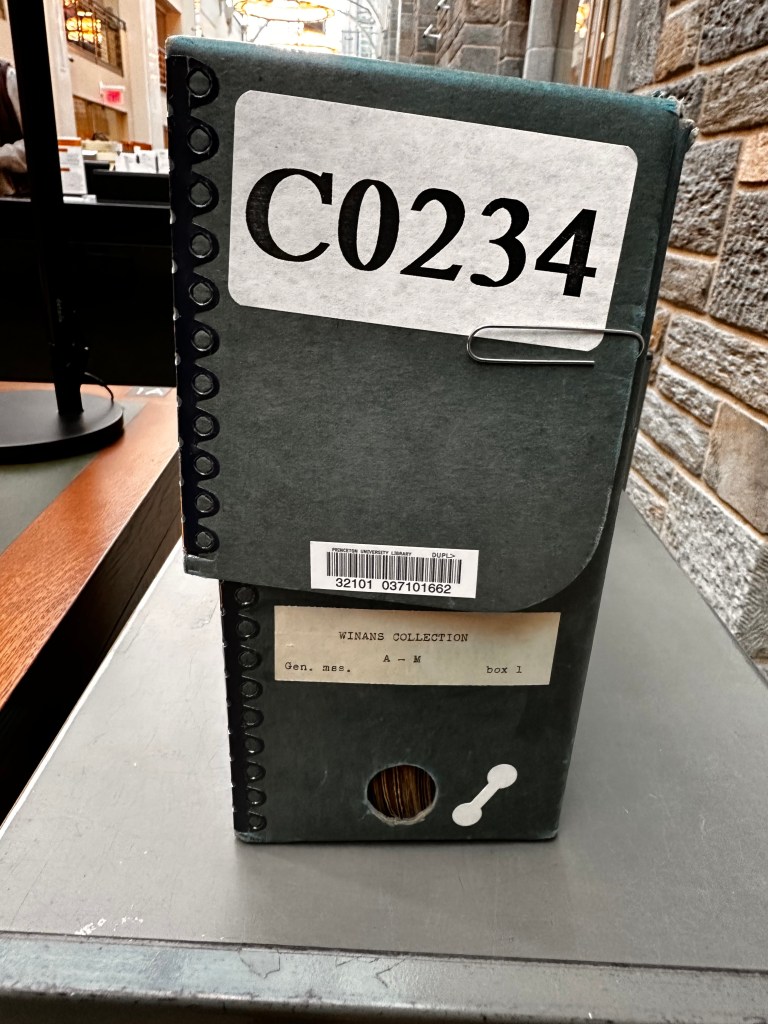

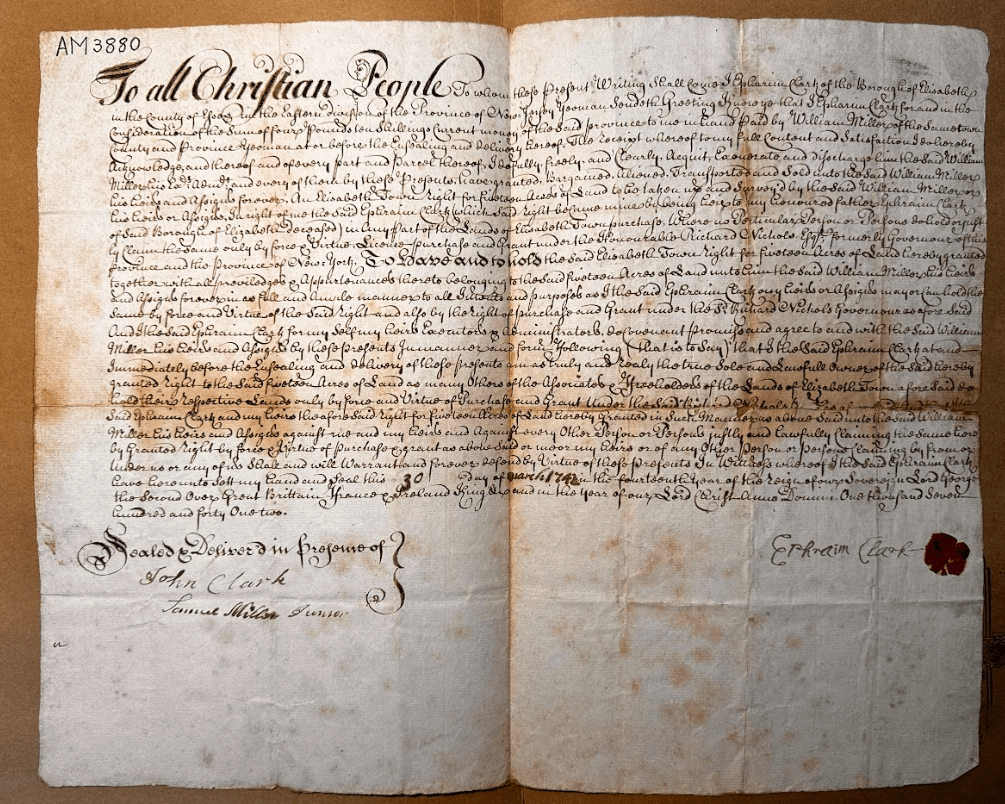

In mid-December, Julia Diddell visited the Special Collections Library at Princeton University to explore the Winans Collection. While sifting through a wealth of primary source materials, she discovered a bill of sale for a young enslaved girl named Jink. This discovery is a valuable addition to Dr. Chewning’s expanding database of enslaved individuals from Westfield, further enriching the ongoing research.

To further her research and make her findings accessible, Dr. Chewning is in the process of creating a website that will feature links to Rutgers and Princeton’s Slavery Projects, offering visitors the chance to explore valuable information and connect with various archives. Stay tuned for updates on the new site!

The Mood Of The Local Inhabitants

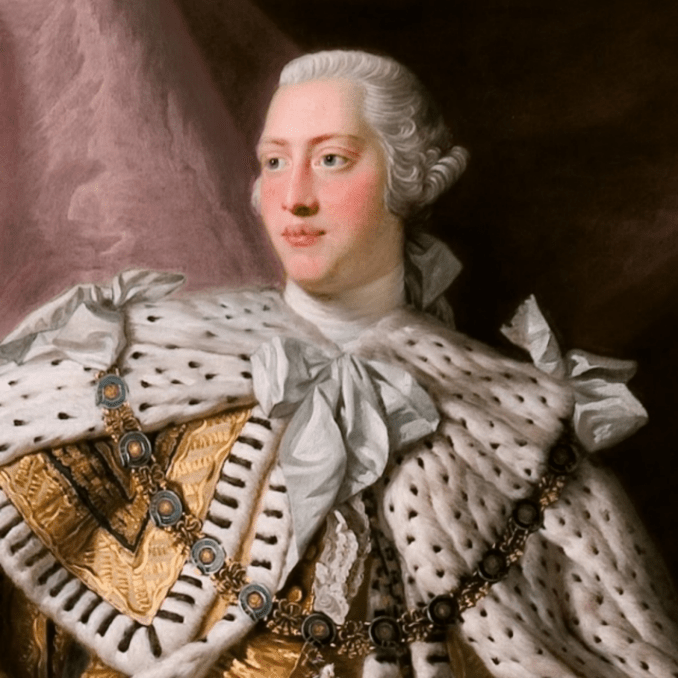

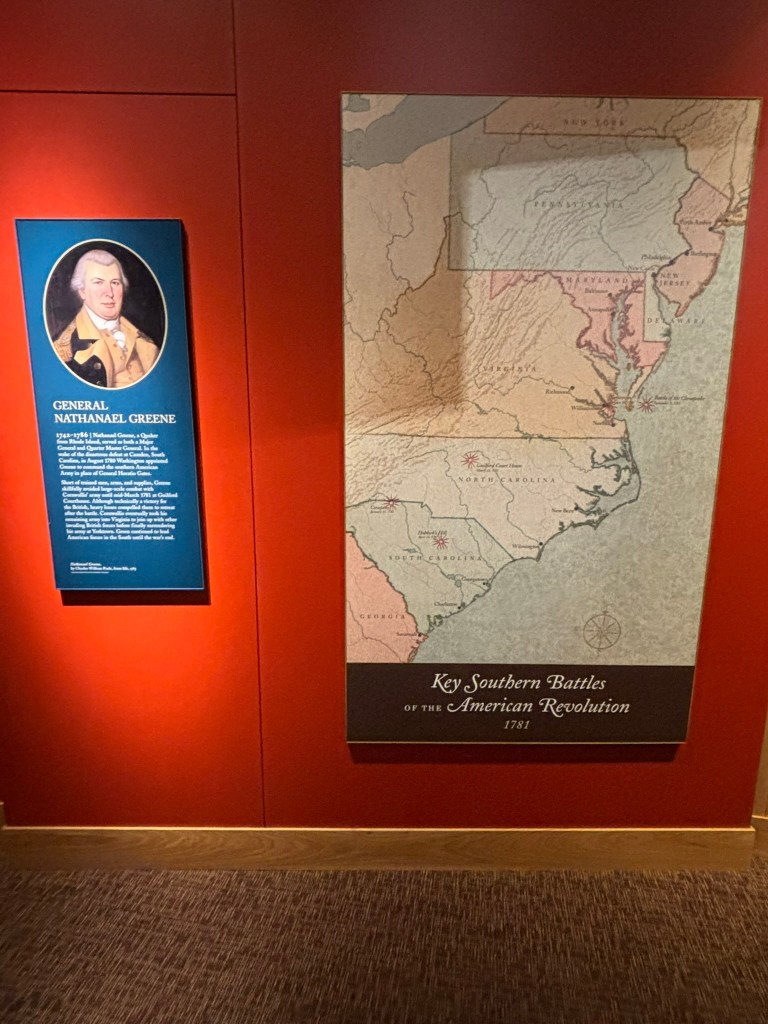

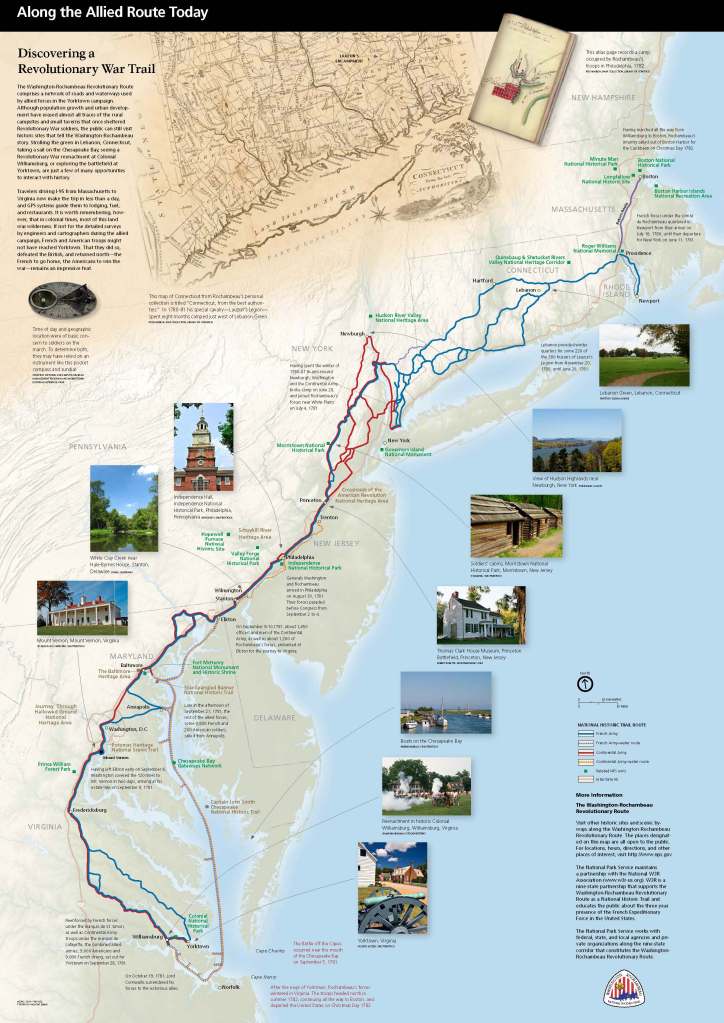

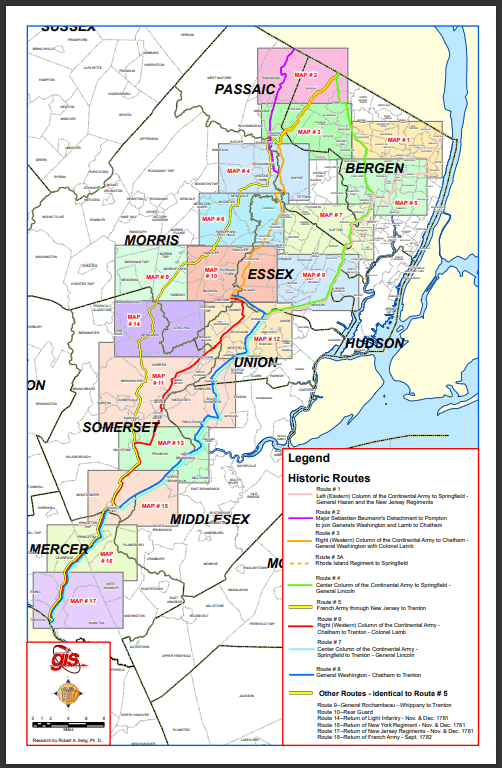

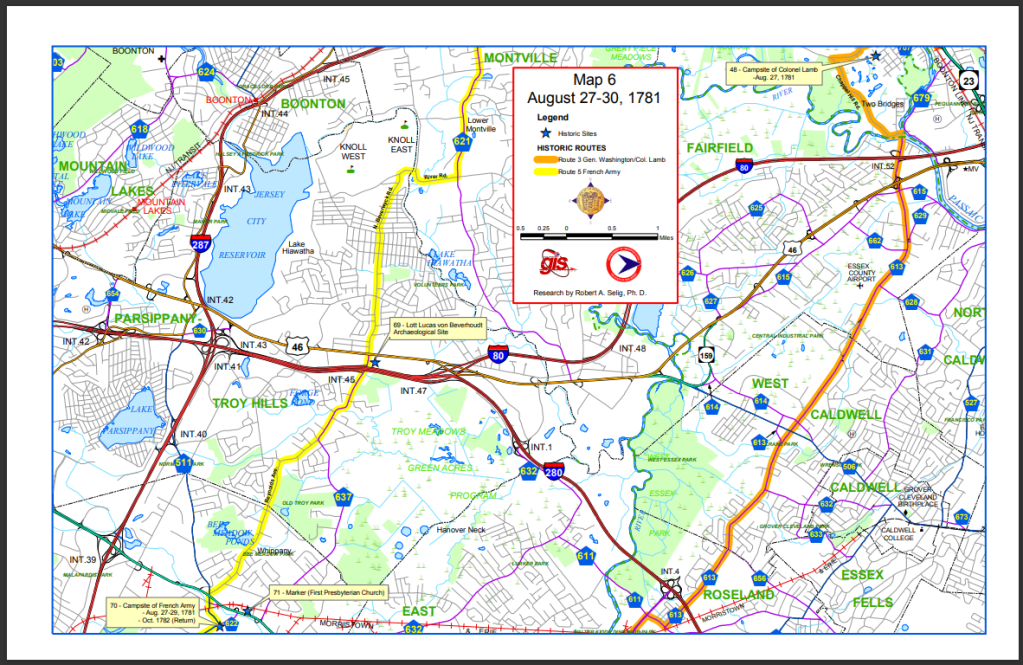

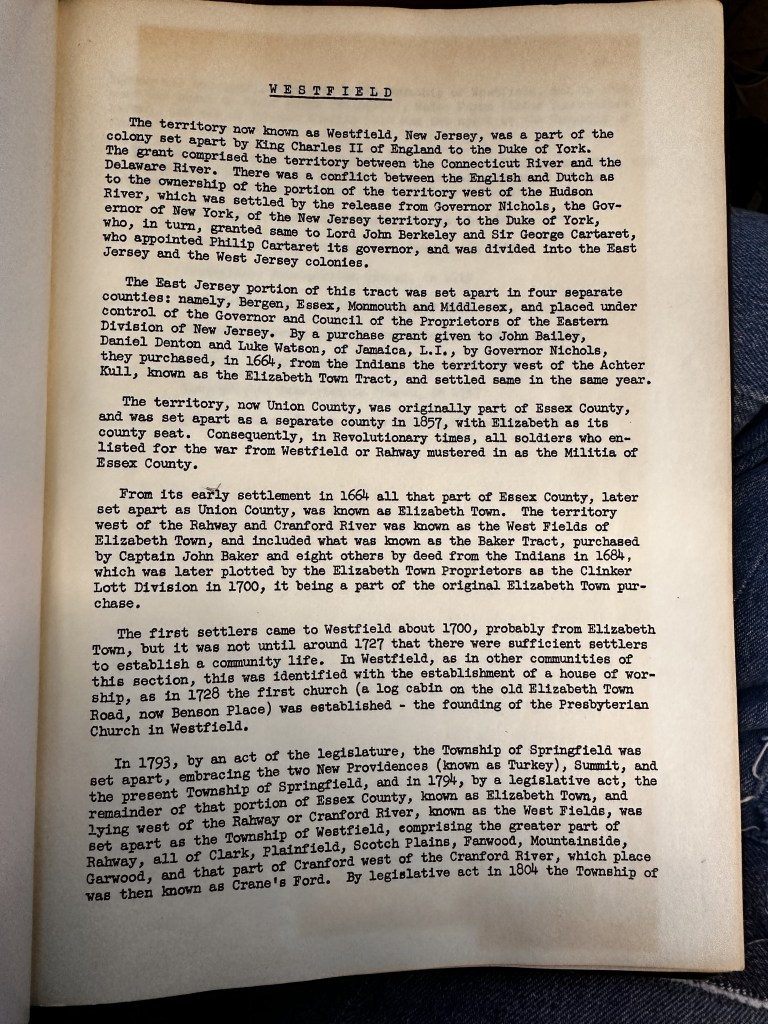

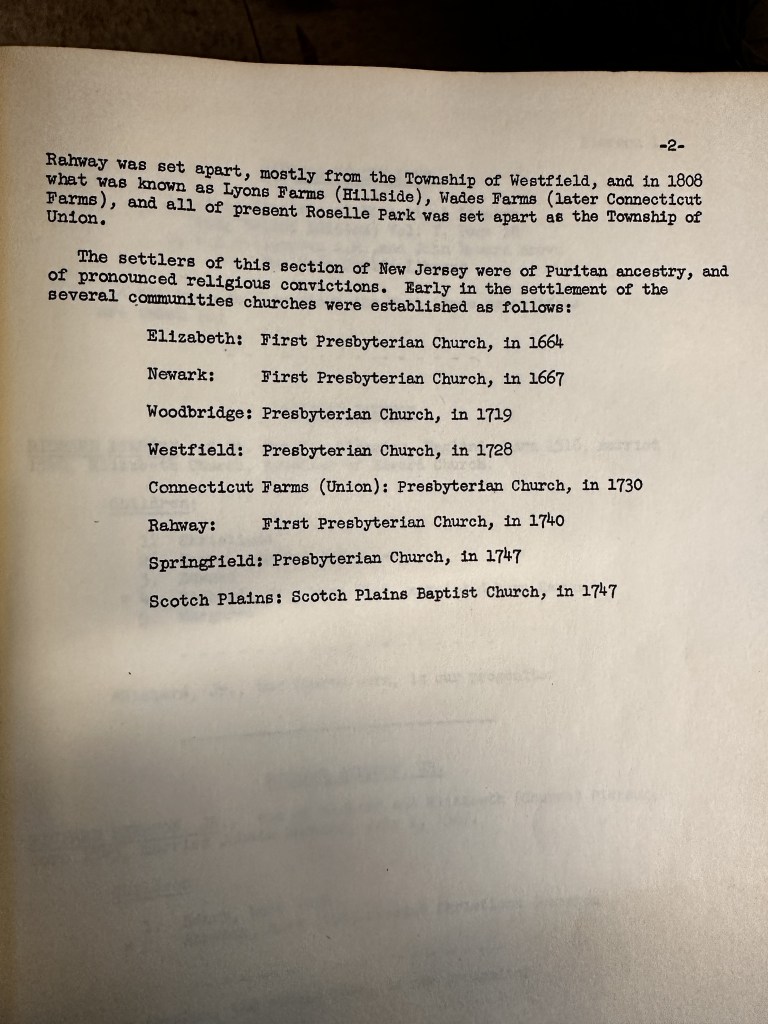

Dr. Robert Selig, a distinguished historian with a PhD in History and extensive experience consulting with the National Park Service, is conducting research on early Revolutionary War activities within Westfield and surrounding towns to gain a better understanding of the mood of the local inhabitants, leading up to the Revolution. Having written extensively on the Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trail, Dr. Selig brings invaluable expertise to the project, particularly in investigating the local impact of the national movement toward independence.

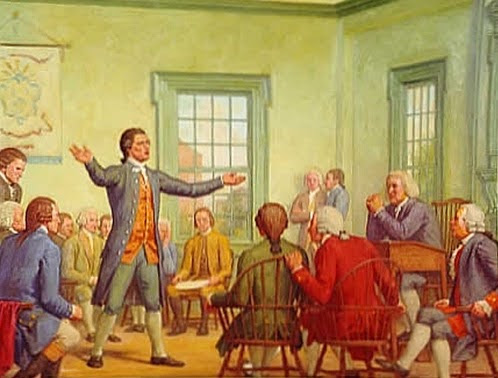

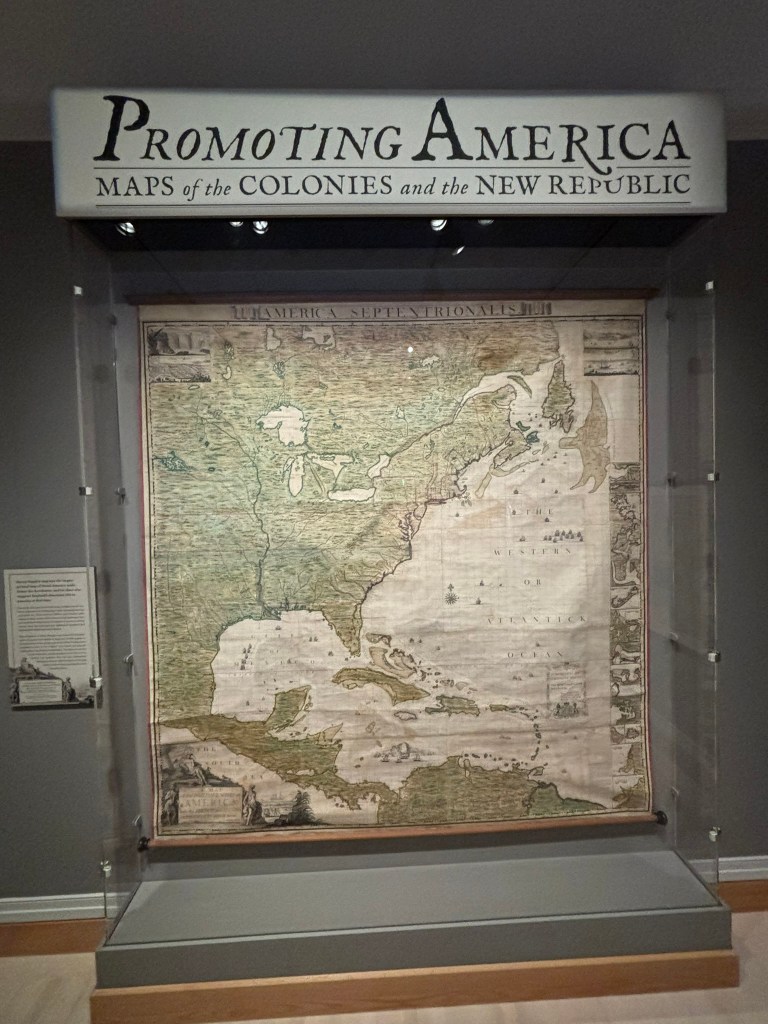

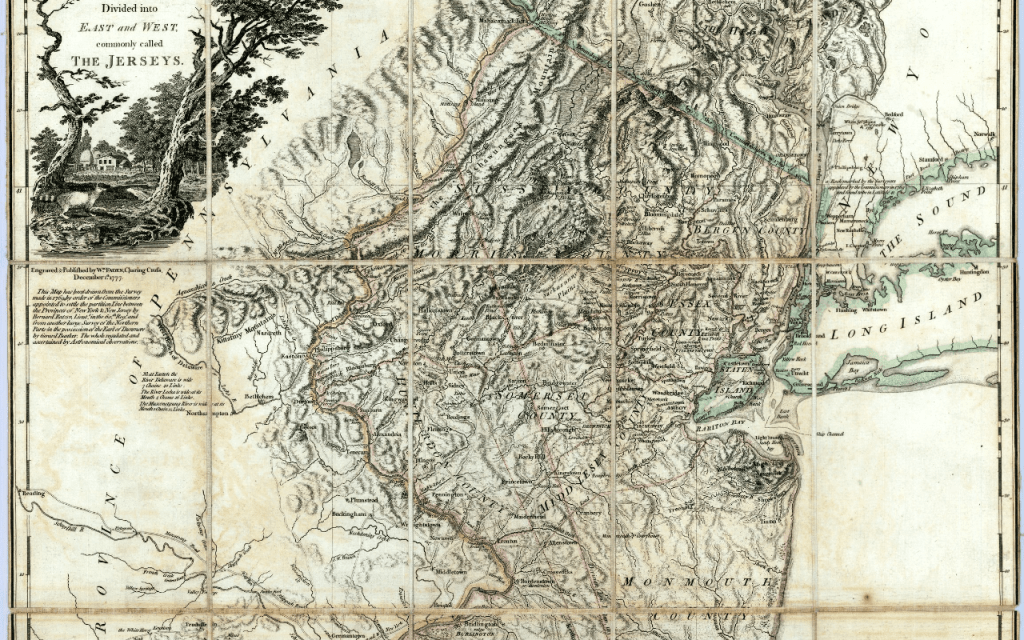

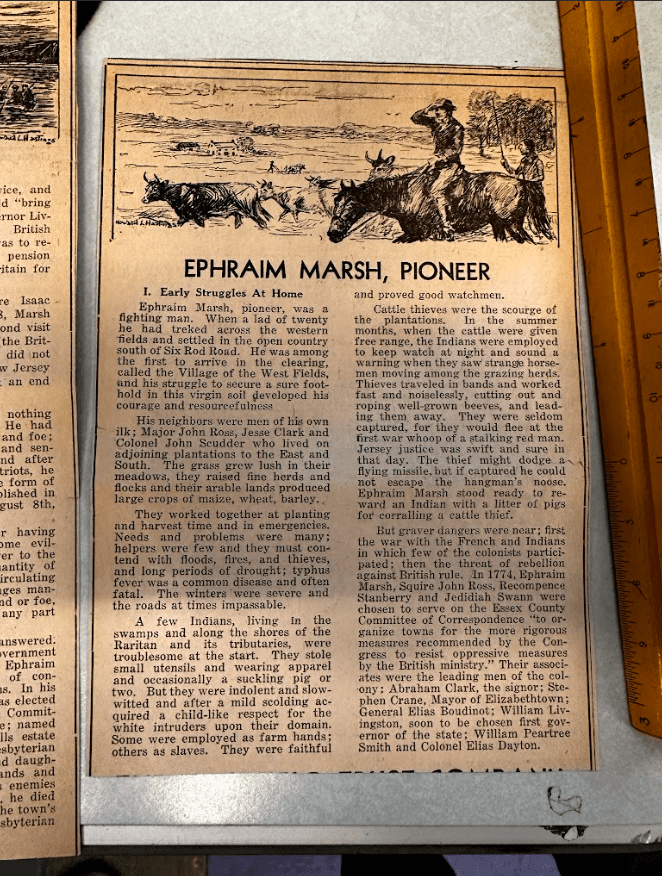

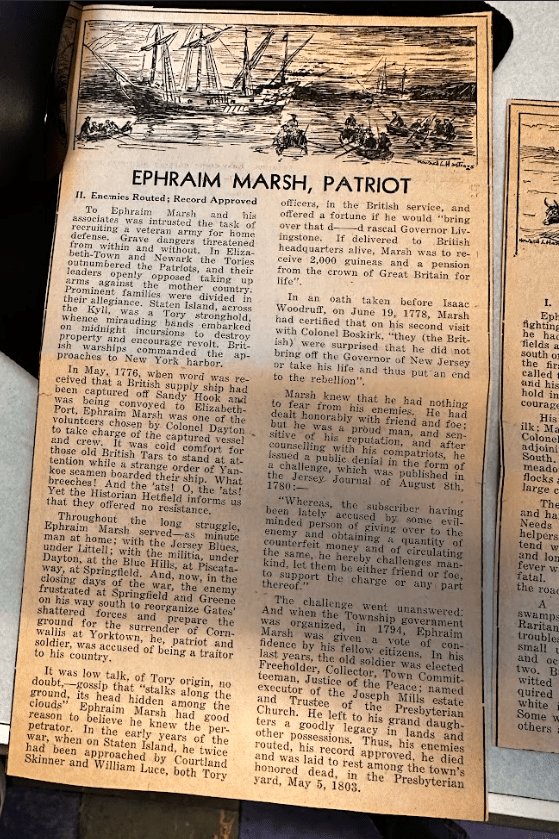

Through his research, he is unearthing not only personal histories but also a broader understanding of the social and political climate of Westfield and surrounding towns in the years leading up to the American Revolution. One key area of focus is the activities of local committees of correspondence- groups that played an essential role in rallying support for independence through the colonies. The committees served as communication networks amongst the prominent leaders of the thirteen colonies. By gaining access to these correspondences, Dr. Selig is uncovering the ways that leaders in New Jersey played a pivotal role in the oncoming Revolution.

Findings So Far

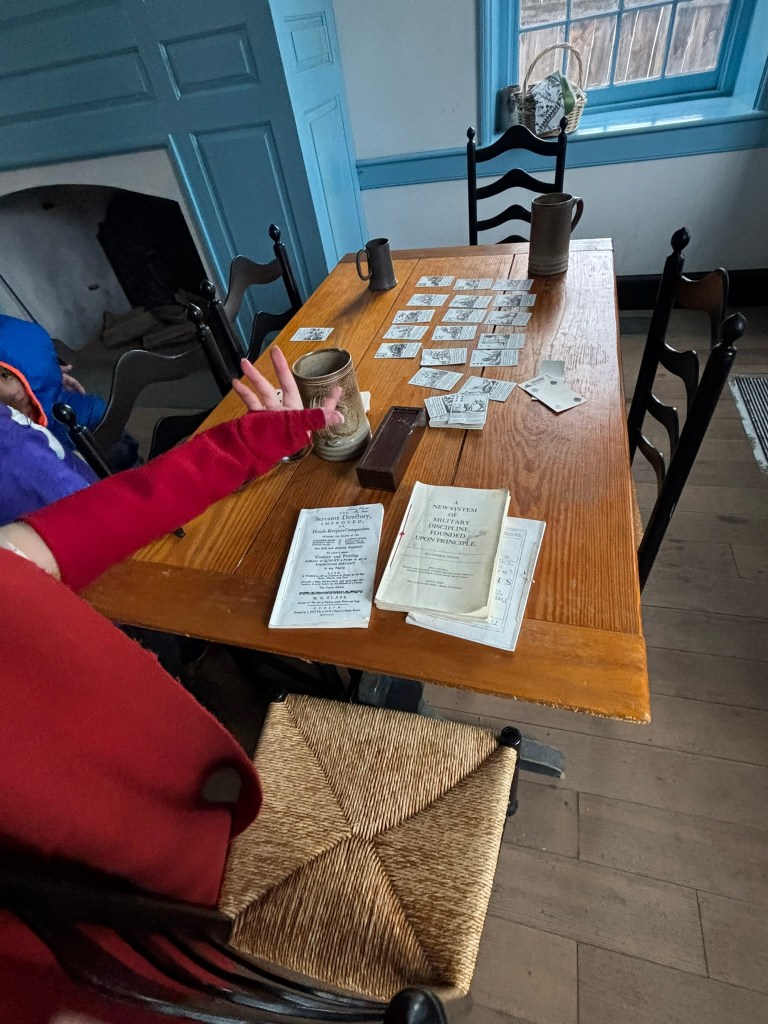

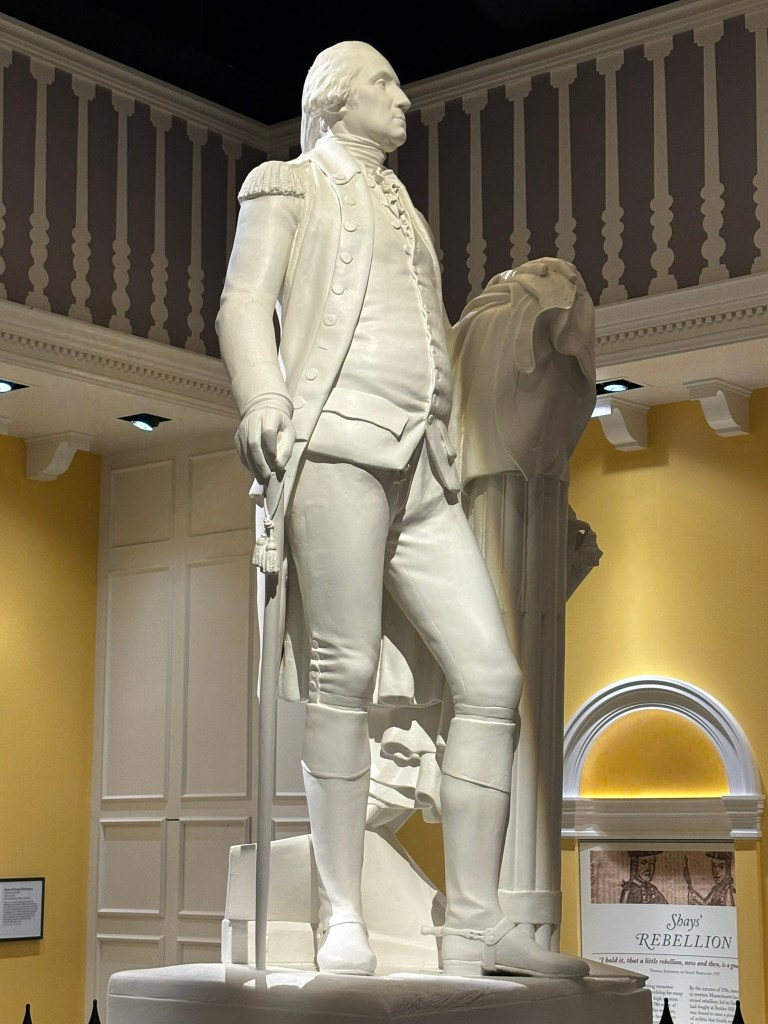

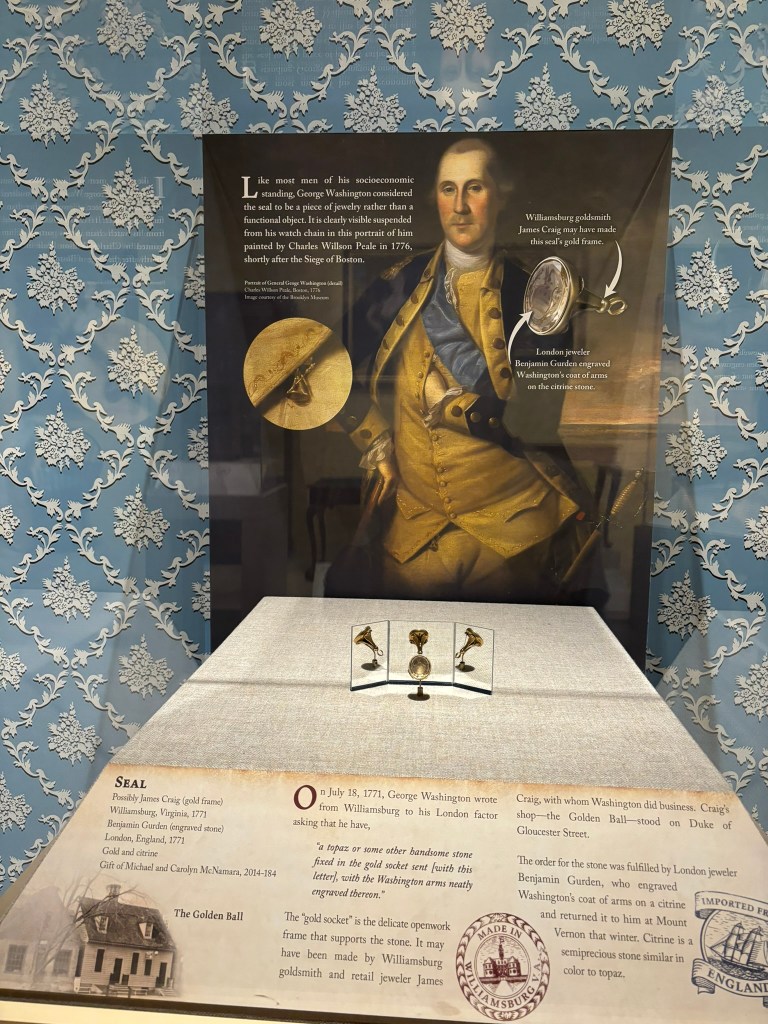

Dr. Selig has been combing through a collection of letters exchanged between New Jersey’s local committees, offering a deeper understanding of the colony’s response to the brewing tensions with Britain. Communications to and from these committees involved notable figures such as George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

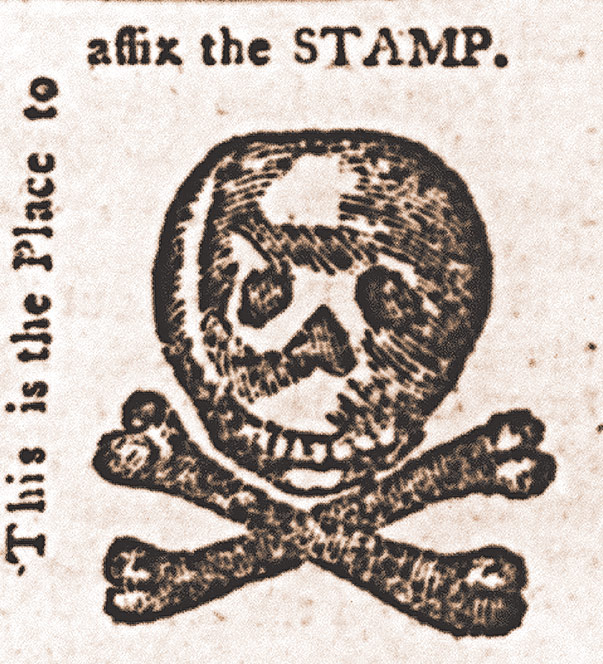

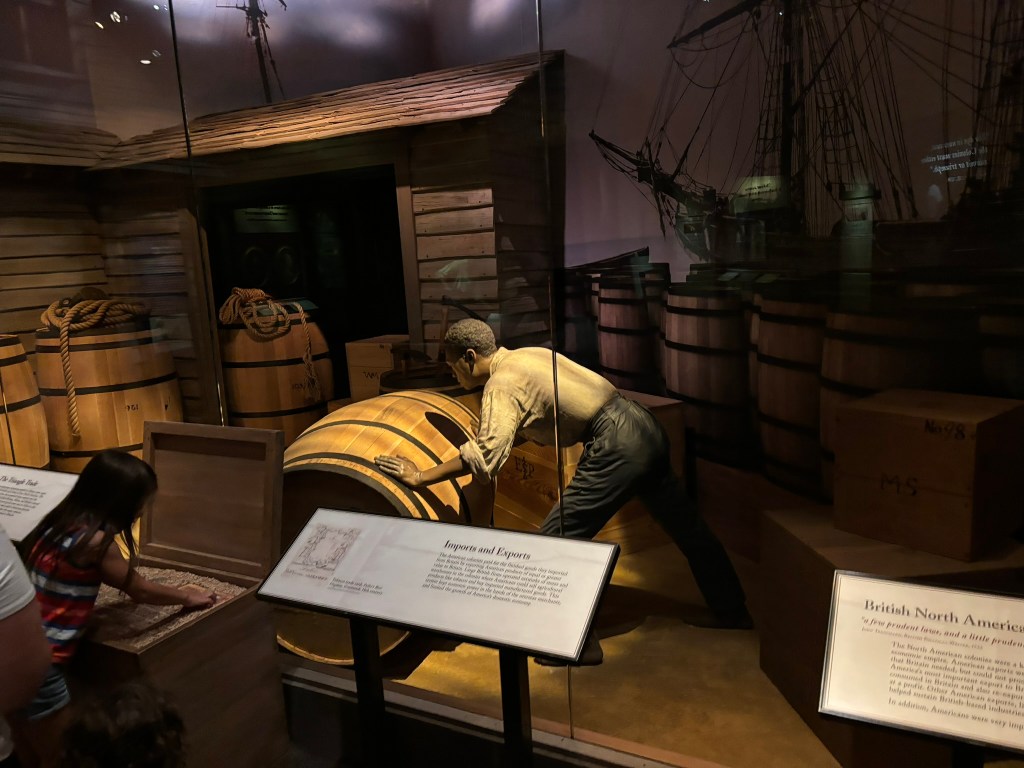

In addition to the Committees of Correspondence, local colonists formed Committees of Public Safety and Committees of Observation. These groups played a pivotal role in the early days of the Revolution, serving as temporary governments and rallying support for the cause. They were responsible for monitoring British actions, enforcing boycotts of British goods, and keeping the colonists united in their resistance efforts.

For Dr. Selig’s research, the exchanges between these committees are invaluable primary sources that help highlight the mood in New Jersey leading up to the Revolution. They reveal not only the political dynamics of the time but also the local efforts to coordinate resistance, making these letters vital in understanding how New Jersey navigated the path toward independence.

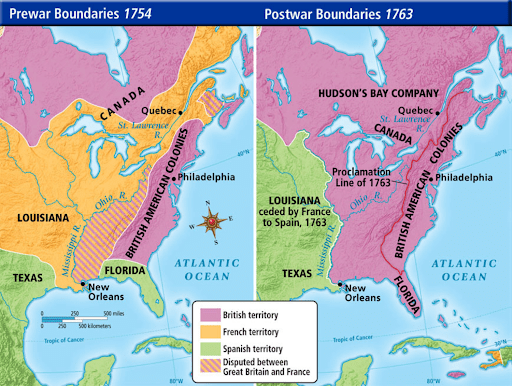

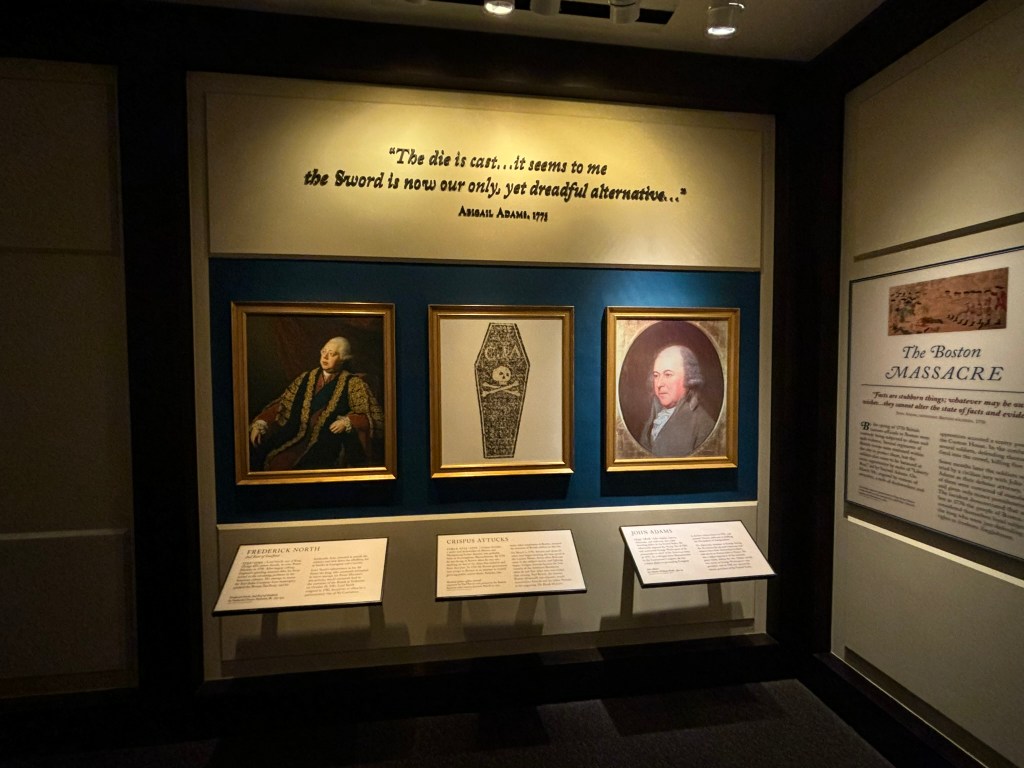

An interesting observation from Dr. Selig’s research is that New Jersey was somewhat slower to embrace the revolutionary movement compared to other colonies, particularly in comparison to the early radicalization seen in places like Massachusetts. Dr. Selig explains that one key reason for this delay was the lack of a large city in New Jersey that could serve as a central political hub. Unlike cities like Boston, which were hotbeds of revolutionary sentiment, New Jersey’s smaller urban centers didn’t provide the same rallying points for activists and leaders. In addition, New Jersey had a popular royal governor who helped maintain a sense of stability.

Through his study of the Committees of Safety, Dr. Selig concludes that New Jersey’s initial concerns were more focused on economic issues than on spreading revolutionary ideology or politicizing the conflict. The colony’s focus on economic stability meant that it took a more cautious approach to the growing tensions with Britain, with many colonists more concerned about their livelihoods than the broader political shifts happening in other parts of the colonies.

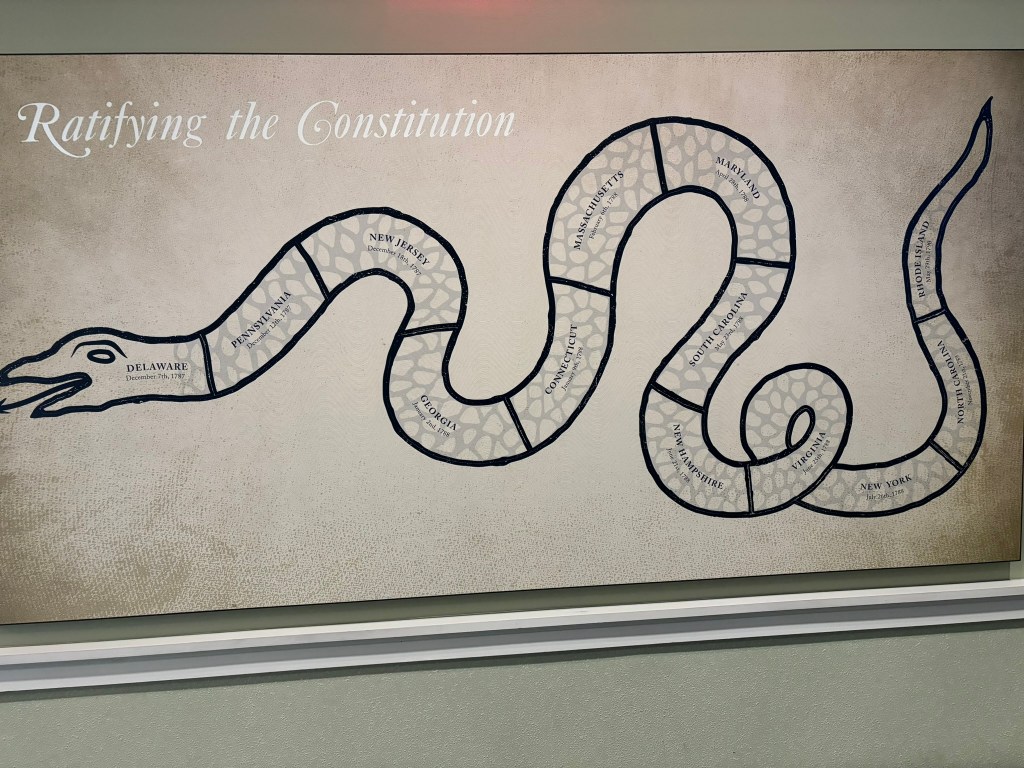

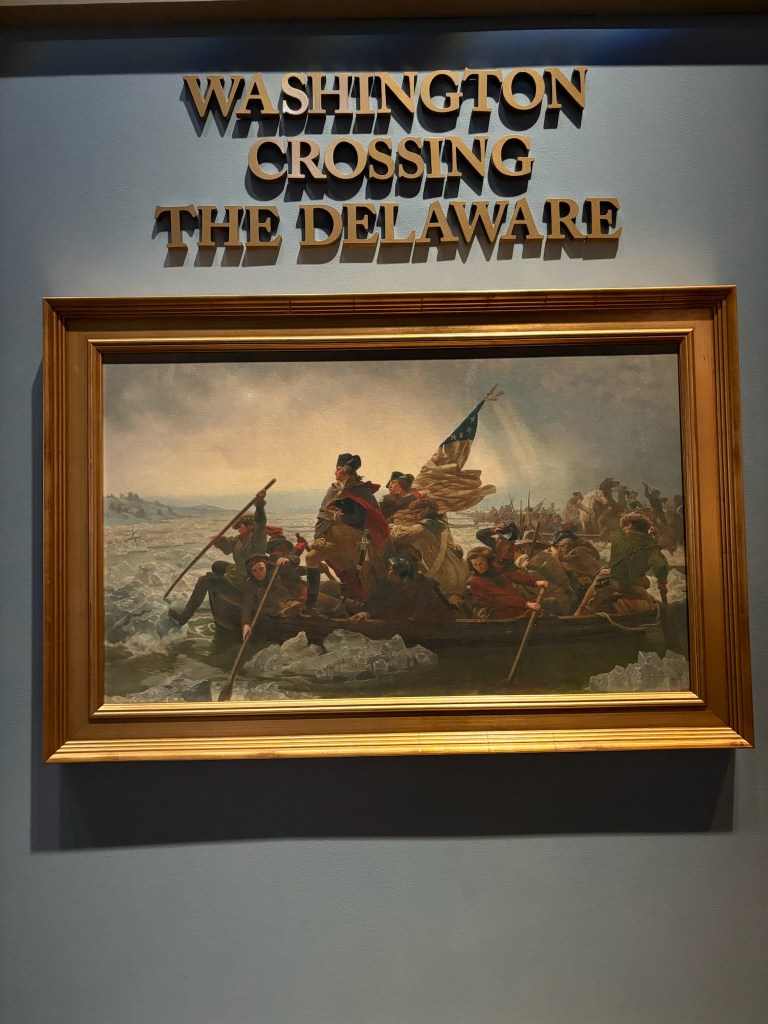

Dr. Selig discovered a significant shift in New Jersey’s stance once the fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord in 1775, as neutrality became increasingly untenable. With battles erupting, colonists found themselves compelled to take sides as remaining on the sidelines was no longer an option.

For many, joining the militia and taking up arms became a clear political statement. By fighting in the militia, New Jersey residents were publicly aligning themselves with the cause of independence and supporting the Declaration of Independence. This shift marked a turning point in the colony’s involvement in the Revolution.

Dr. Selig’s research into New Jersey’s role in the American Revolution is ongoing. He is actively seeking more primary sources to deepen his understanding of the colony’s shift toward supporting the war effort. In particular, Dr. Selig is interested in diaries, letters, and other personal documents from both local leaders and everyday inhabitants of towns like Westfield. These materials, he believes, will provide crucial insights into the changing attitudes and the personal motivations that led people to join the war.

Dr. Selig is also eager to uncover other types of historical documents, such as pension applications, damage claims, and even tavern records. These records can offer a unique perspective on the war’s impact at the local level, shedding light on the economic and social effects of the conflict.

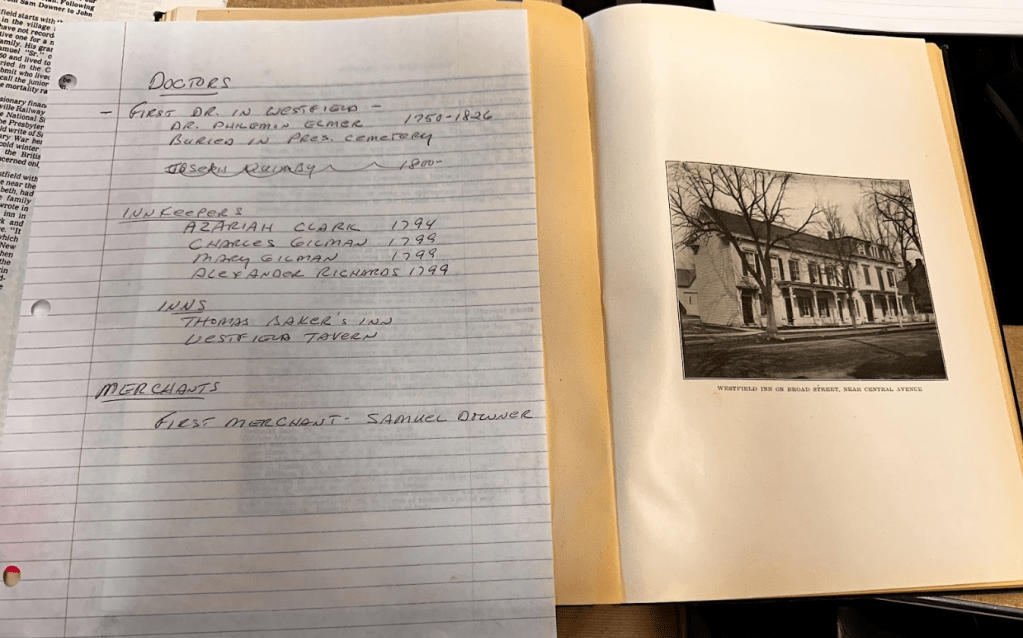

The researchers plan to collaborate in order to link their research efforts together. Beyond the primary documents already mentioned in this article, the research team is drawing from a variety of additional sources, including histories of Westfield, ledgers, lists of local doctors, innkeepers, and merchants, as well as records detailing key regional figures. They’re also studying militia payrolls from Essex County, personal letters, and the names of Revolutionary soldiers buried at the Westfield Presbyterian Church.

Building A Lasting Legacy

One of the aims of this research project is to create a lasting educational resource for the community. The team is exploring the possibility of an enduring outdoor exhibit or monument that would allow the public to engage with this history in a meaningful way. The groundwork is now being laid for this educational space that honors the notable figures who played an impactful role in Westfield and surrounding towns at the time of the American Revolution.

Stay tuned as the Westfield Historical Society continues this important work and opens the door to a richer, more inclusive understanding of our shared past. I will be posting another blog at the conclusion of this research project. As mentioned above, there will be a Hybrid Presentation in June by the research team where further findings will be revealed, providing the public with a deeper understanding of the people and events that have shaped this community for centuries. You will not want to miss this! Stay tuned and stay connected with the organizations listed below that are involved in this research:

Check out these related posts: