In a previous blog post entitled “The Inclusive History of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Trail Phase II – Westfield, NJ (Part 1)”, I shared an overview of an ongoing history research project conducted by the Westfield Historical Society, with support from the New Jersey Historical Commission. The research has been conducted by Dr. Susannah Chewning and Dr. Robert Selig, and it aims to uncover untold stories and to shed light on both free and enslaved inhabitants of the greater Westfields of Elizabethtown and their roles during the time of the American Revolution.

If you haven’t had a chance to read the first blog post from February 7th, 2025, I encourage you to check it out [HERE]. It offers valuable context about the project’s background, goals, and initial findings.

This blog post picks up where the previous one left off. Since February, the research has entered a new phase, bringing to light fresh insights and raising new questions that have continued to guide the direction of the work. In this update, I’ll share the latest progress, some of the challenges encountered, key discoveries made, and an overview of the final presentation which took place on June 21st, 2025.

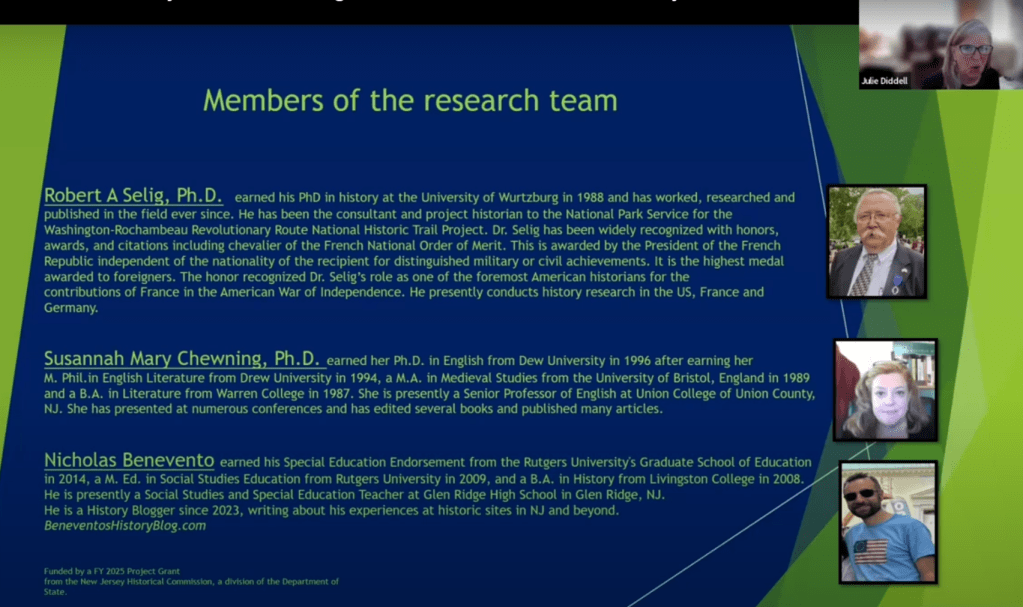

The researchers have been working closely with Julia Diddell, Chair of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route- New Jersey, as well as Brian Remite, President of the Westfield Historical Society, to comb through enlightening resources. The team met in late March to discuss new findings, challenges along the way, and future goals. The team was also joined by Dr. Mary Konsolaki and Dr. Ken Mirsky, who both serve on the Grants Committee at the Westfield Historical Society.

The team reconvened in mid-May, with each researcher sharing their latest findings, describing any new obstacles, and discussing plans for the final presentation. During the meeting, Julia shared that the Westfield Historical Society is interested in using the research to develop a long-term outdoor exhibit in Westfield. She also noted that the Society is planning to collaborate with the Rutgers Department of Landscape Architecture to explore potential sites for the exhibit and may even conduct a survey this summer.

The information provided below provides the latest updates on the research and discoveries of Dr. Robert Selig and Dr. Susannah Chewning, covering their progress from April 2025 to the final outcomes of the research project, concluding with the presentation to the public. For an overview of their research topics and goals, please refer to the first blog post.

The Mood of the Local Inhabitants

Dr. Robert Selig, a distinguished historian with a PhD in History and extensive experience consulting with the National Park Service, has been conducting research on early Revolutionary War activities within Westfield and surrounding towns to gain a better understanding of the mood of the local inhabitants, leading up to the Revolution. Having written extensively on the Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trail, Dr. Selig has brought invaluable expertise to the project, particularly in investigating the local impact of the national movement toward independence.

April 2025 Update

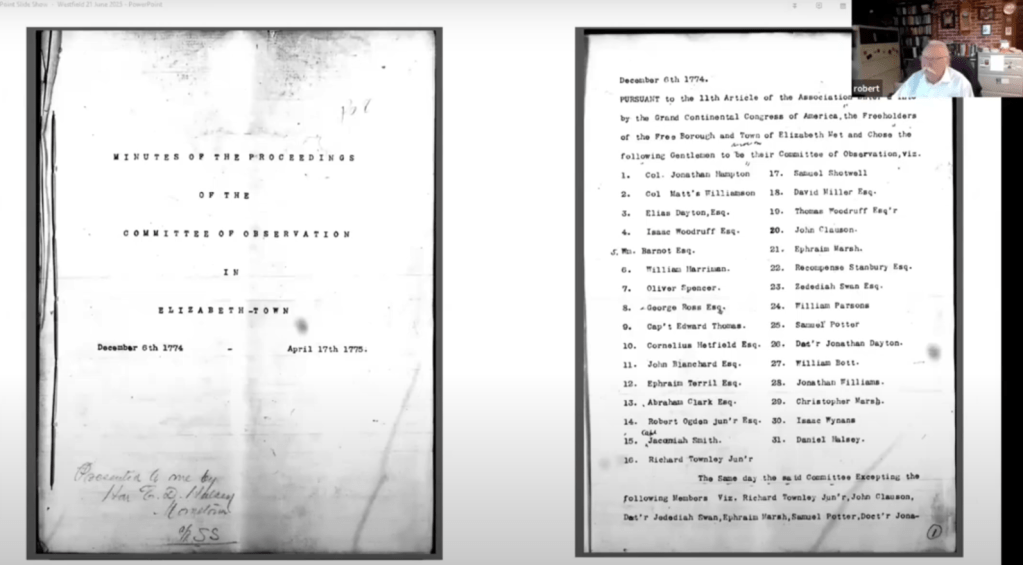

During our late March meeting, Dr. Selig provided updates on his research. He emphasized the importance of identifying individuals on a list from the New Jersey Committee of Correspondence, focusing on their economic status and roles within the community. Dr. Selig has accessed damage claims from the New Jersey State Archives, revealing that seven of the ten Westfield Committee members filed claims—though notably, Abraham Clark, a key regional leader and signer of the Declaration of Independence, did not. These claims provide valuable insights into the local inhabitants. Moving forward, he also intends to study New Jersey citizens who served in the war, particularly through pension applications from soldiers and members of the New Jersey militia, which could offer significant insight.

In early April, Dr. Selig had the opportunity to visit Rutgers University’s Special Collections Library to continue his research, and on his second day, he made a significant discovery—the Jedediah Swan Papers. Dr. Selig found some 500 documents, including letters, indentures, and other records, spanning nearly 75 years of Swan family history, from Amos Swan in the 1760s to Jedediah’s death in the 1820s. Many of the papers referenced Westfield as either the origin or destination. Jedediah Swan (1732–1812) is buried in Scotch Plains.

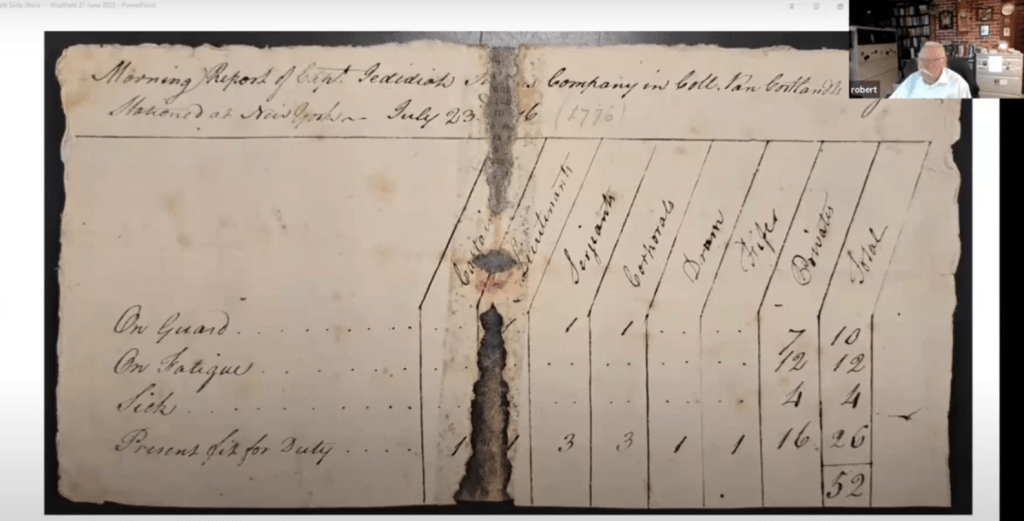

Jedediah Swan was an MD, Justice of the Peace, Overseer of the Poor, Committee of Correspondence member, Captain of the Second Regiment Essex County Militia, and held several other roles. Dr. Selig photographed about a dozen documents that will help the researchers reconstruct Swan’s influence in the community. Among the findings were an enlistment paper for a soldier in his company, a record committing a poor woman to the town’s care, a case involving an unwed mother and the man she accused of fathering her child, a note mentioning his enslaved individual, Dorceas, and a receipt for expensive beaver-fur hay. These findings help paint a picture of a man who was influential in the Revolutionary movement in the Westfields.

May 2025 Update

During our May meeting, Dr. Selig discussed the book War in the Countryside: The Battle and Plunder of the Short Hills, New Jersey, June, 1777. Vol. I by Frederic C. Detwiller, which includes references to Jedediah Swan and cites the “Marsh Papers,” housed at the Plainfield Historical Society. The team described their efforts to contact the Society and locate these papers, which may contain valuable information about Swan. This example highlights the researchers’ diligence and the many challenges they navigated—acting as historical detectives, following promising leads. It’s been truly impressive to watch the team support one another and collaborate so effectively.

Presentation Day- June 21st, 2025

On June 21st, the research team presented its findings to the public via a Zoom webinar, now available to watch on YouTube [HERE]. I highly encourage you to view the full presentation to get a comprehensive look at the project and its exciting discoveries.

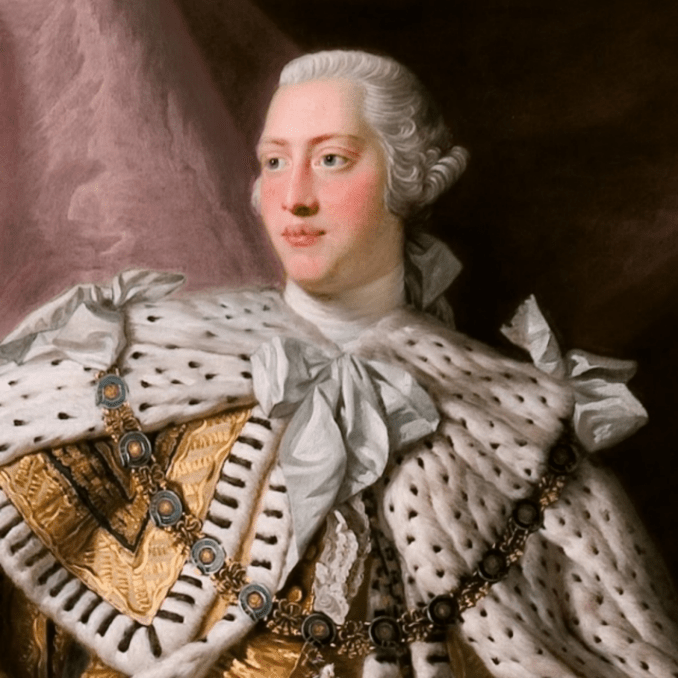

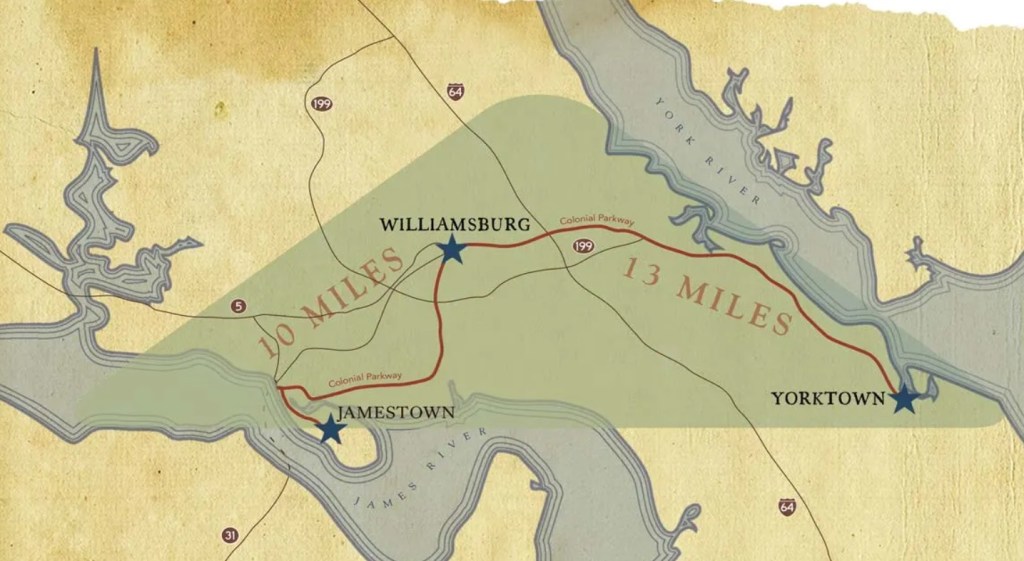

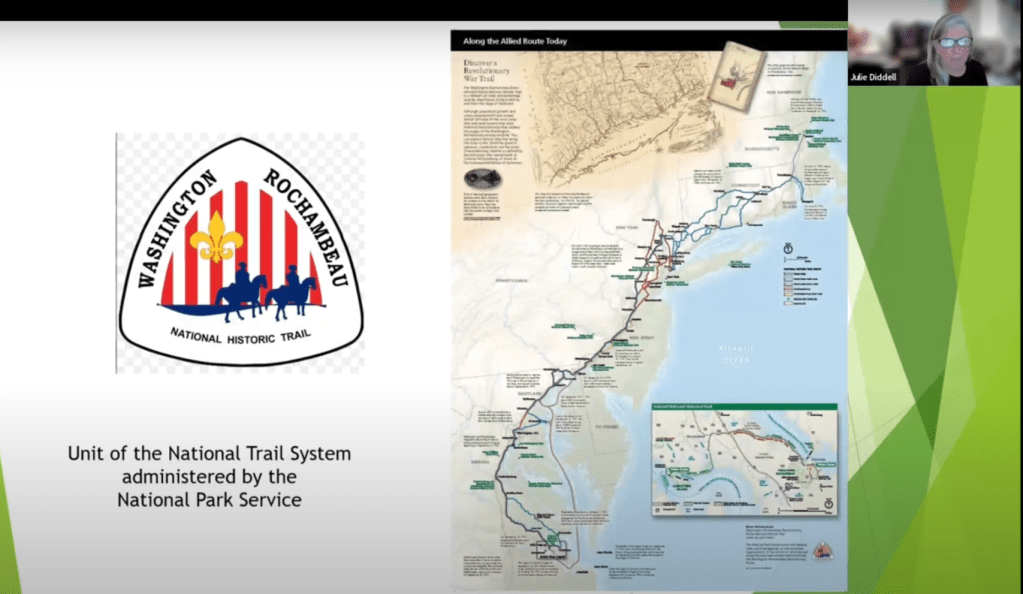

The session began with remarks from Julia, Project Manager and Chair of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route – New Jersey. She outlined the project’s goals, provided a historical overview of the Revolutionary War, described the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route, and discussed its lasting impact on the local community. Julia also introduced each member of the research team before transitioning to a pre-recorded video presentation by Dr. Selig.

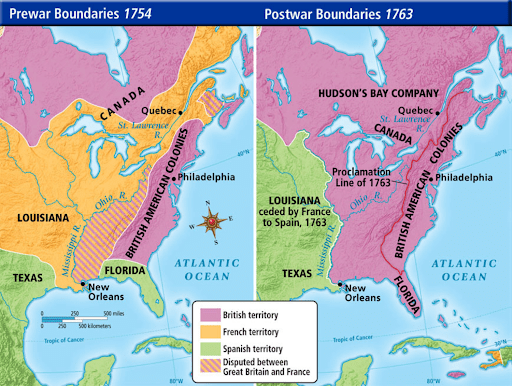

In his presentation, Dr. Selig shared the objectives of his research, which focused specifically on Westfield, New Jersey. His goals included identifying residents who served on the Essex County Committee of Correspondence, documenting the sentiments of local inhabitants in the lead-up to the Revolution—particularly in the area then known as the West Fields of Elizabethtown—and analyzing pension applications and other historical documents from Westfield veterans of the War of Independence.

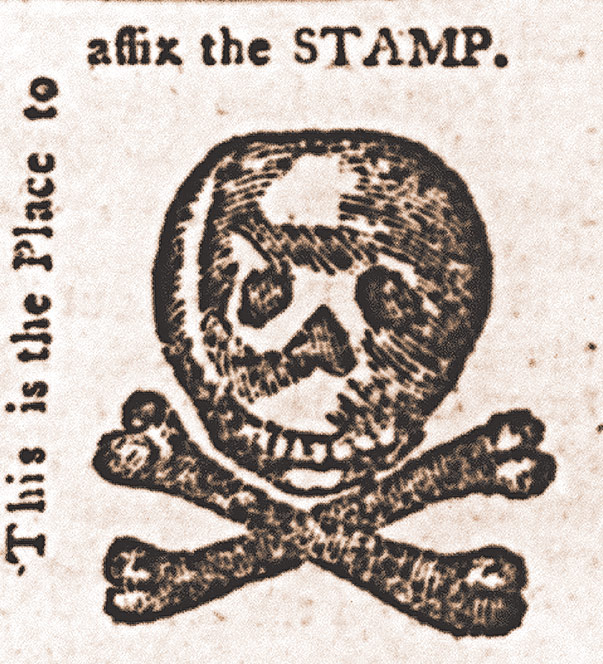

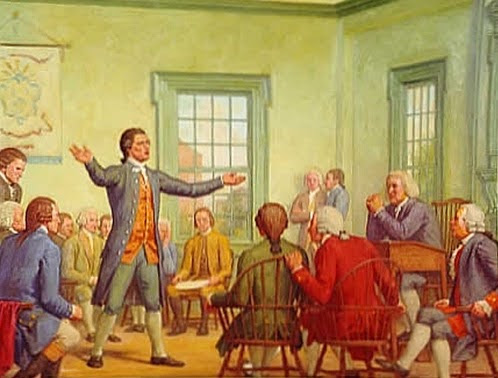

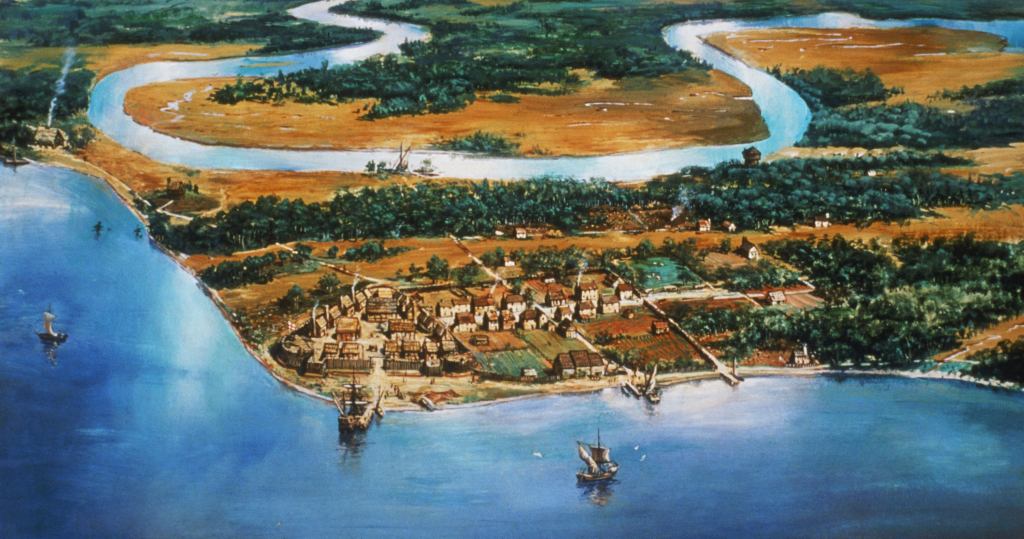

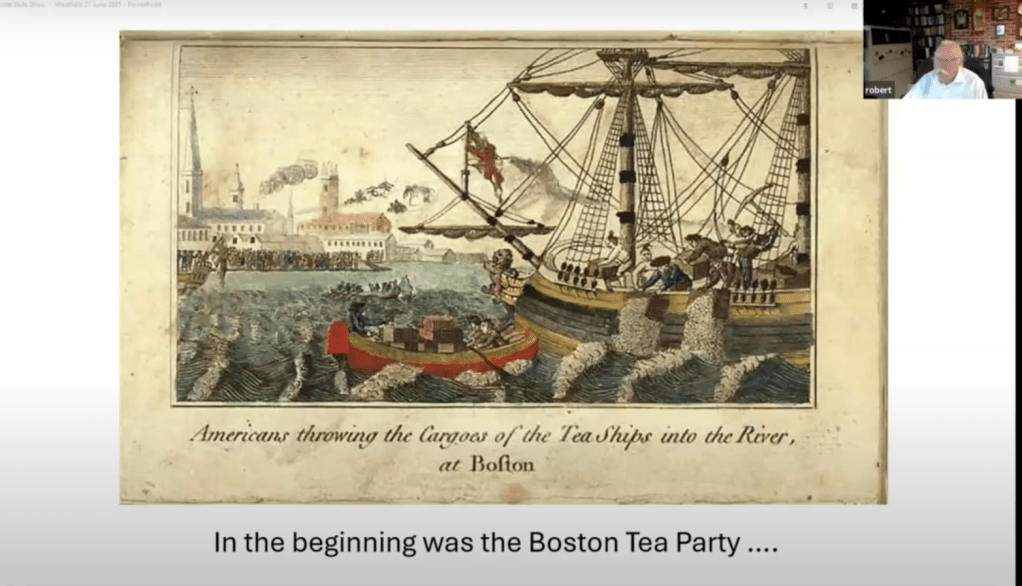

To set the historical context, Dr. Selig began with the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773. In response to this act of defiance, the British government passed the Intolerable Acts, aimed at punishing the colonies—especially Massachusetts. This prompted the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence to call upon other colonies to join a boycott of British goods. For New Jersey, this marked the first major action taken by its own Committee of Correspondence in support of a united colonial resistance.

Dr. Selig described how meetings were held throughout New Jersey to coordinate responses to British policies. Delegates from various counties gathered in towns such as New Brunswick and Elizabeth. He identified several representatives from the Westfield area who attended these meetings—men who were part of the local elite and played influential roles in shaping public sentiment. Through primary source materials, Dr. Selig offered insight into who these leaders were, including damage claims they filed during the war.

A particularly notable figure discussed was Jedediah Swan. As mentioned above, Dr. Selig uncovered significant information about Swan during his research at Rutgers University, including original documents that shed light on his contributions during the Revolutionary era. Swan’s story illustrates the importance of individual actors in the broader historical narrative.

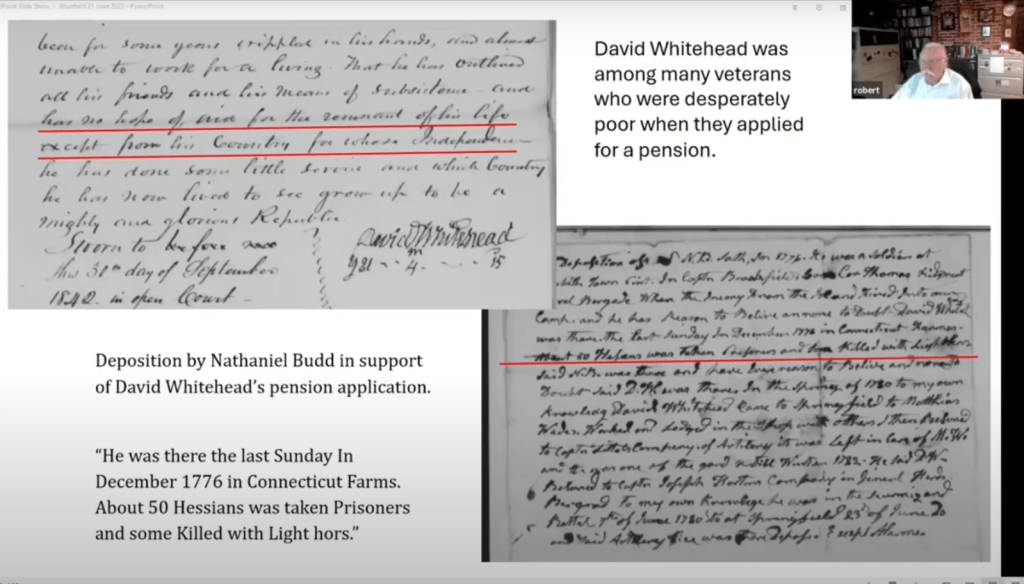

Dr. Selig also explored the wartime experiences of ordinary Westfield citizens through pension applications filed under the Federal Pension Act of 1832. He transcribed approximately 25 applications from Westfield veterans, noting that many more remain. These documents offer a rich look into both the war and its long-term effects on those who served. For example, one application recounted the capture of Hessian soldiers, while another revealed the desperate financial condition of veteran David Whitehead at the time of his filing. Some veterans described fleeing their homes during British raids. These accounts provide a deeply personal view of how the war affected individuals and families, both during and long after the conflict ended.

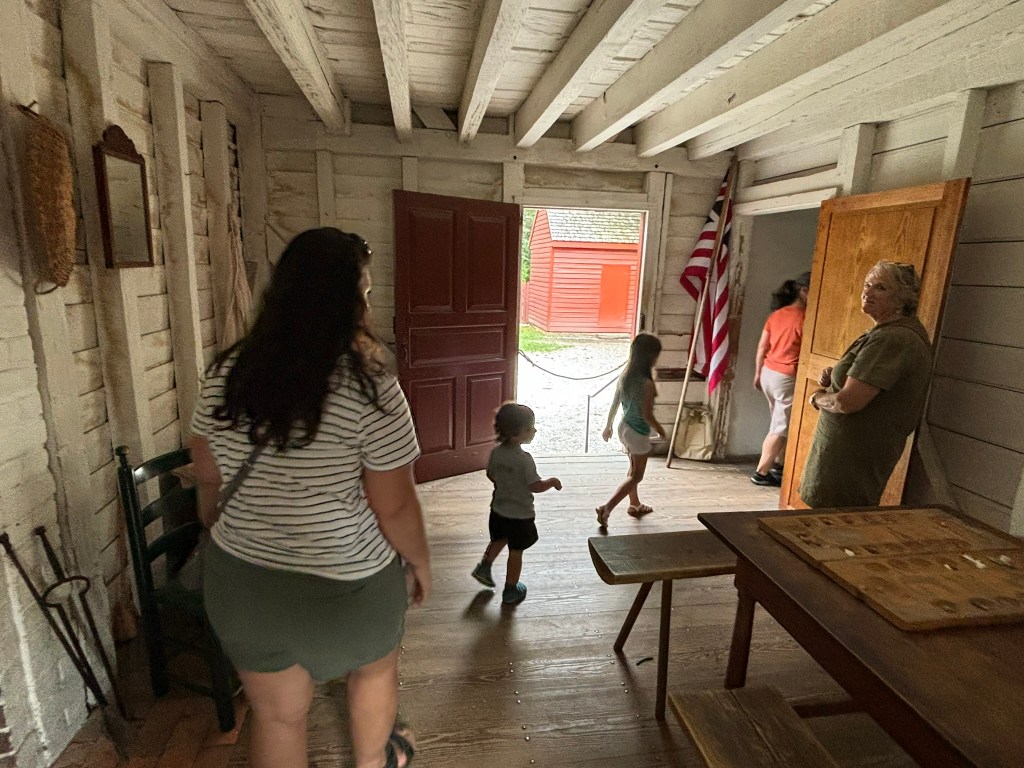

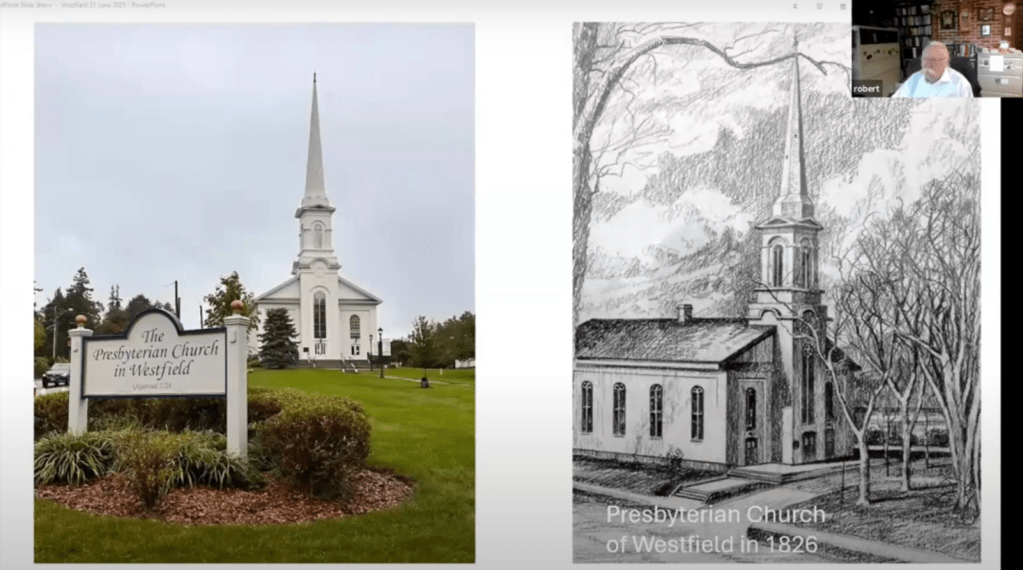

Another important highlight from Dr. Selig’s presentation was the Miller-Cory House, located in Westfield along the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route. The house was built by Clark Miller, who served in the Continental Army for two years and six months. He is buried in the cemetery of the Westfield Presbyterian Church, connecting a local landmark to national history in a profound way.

Dr. Selig concluded his presentation by summarizing his key themes, including the formation of the Committees of Correspondence and the development of local militias—both essential to understanding early American resistance efforts in the local community.

Dr. Selig’s presentation is a compelling and informative look at Westfield’s pivotal role in the Revolutionary War and a testament to the value of local history in understanding our nation’s past.

A Focus on African American History

Research has been conducted that has focused on the African American community in Westfield and the surrounding towns during the Revolutionary Period. Dr. Susannah Chewning, a Senior Professor of English at the College of Union with a diverse academic background in English Literature and Medieval Studies, has been leading this important aspect of the project. Dr. Chewning has been exploring local records, including manumission documents and birth certificates to trace the lives of African Americans in the region. She is working to compile a comprehensive database from her work.

April 2025 Update

During our late March meeting, Dr. Chewning referenced a pre-Revolutionary-era taxable inventory/ census document shared by Julia. She noted her plans to visit Princeton University to examine the full document, as it includes references to enslaved individuals. This information will help her identify who was living in the area at the time and expand her database of African American residents. She also pointed out that some of the enslaved individuals listed were recorded as tax-exempt.

Dr. Chewning noted that when her research first began, she had identified 25 enslaved individuals who lived in Westfield between 1778 and 1781—most of them by name. That number has since grown to 69. Dr. Chewning also discussed a well-known, formerly enslaved woman named Jude, who is buried at Fairview Cemetery in Westfield. Dr. Chewning believes she has identified Jude’s parents, offering another valuable lead in tracing individuals who were alive during the March to Yorktown in 1781.

Dr. Chewning recently presented her research at her college and at the New Jersey College English Association Annual Conference, where it was well received. While at the conference, she attended a Digital Humanities Workshop sponsored by the New Jersey Humanities Consortium, which provided valuable insights for the development of her website (featured in the first blog post). Inspired by the workshop, Dr. Chewning is now exploring the idea of launching a podcast. She envisions using the platform to interview descendants of formerly enslaved individuals from the Westfields, as well as researchers and historians. Although still in the early planning stages, she is already brainstorming episode ideas. In addition, she connected with members of other New Jersey counties working on similar projects and is considering a long-term initiative to honor the African Americans who lived in the region during the Revolutionary era.

As part of her efforts to locate the burial sites of African Americans, Dr. Chewning noted that when Fairview Cemetery was established in 1868, many bodies were relocated from the Old Presbyterian Church burial ground. She plans to continue her research to determine who was moved and the reasons behind those relocations.

May 2025 Update

During our May meeting, Dr. Chewning shared her latest research efforts in preparation for the upcoming June 21st presentation. She mentioned her ongoing plans to visit Fairview Cemetery to investigate additional burial sites and uncover more information about African Americans buried there. She also spoke with Julia about plans to create a permanent public outdoor display that will showcase the researchers’ work.

Presentation Day- June 21st, 2025.

After Dr. Selig presented his findings, Dr. Chewning had the opportunity to share her own research with the public. She began by introducing herself and explaining how she became involved in the project.

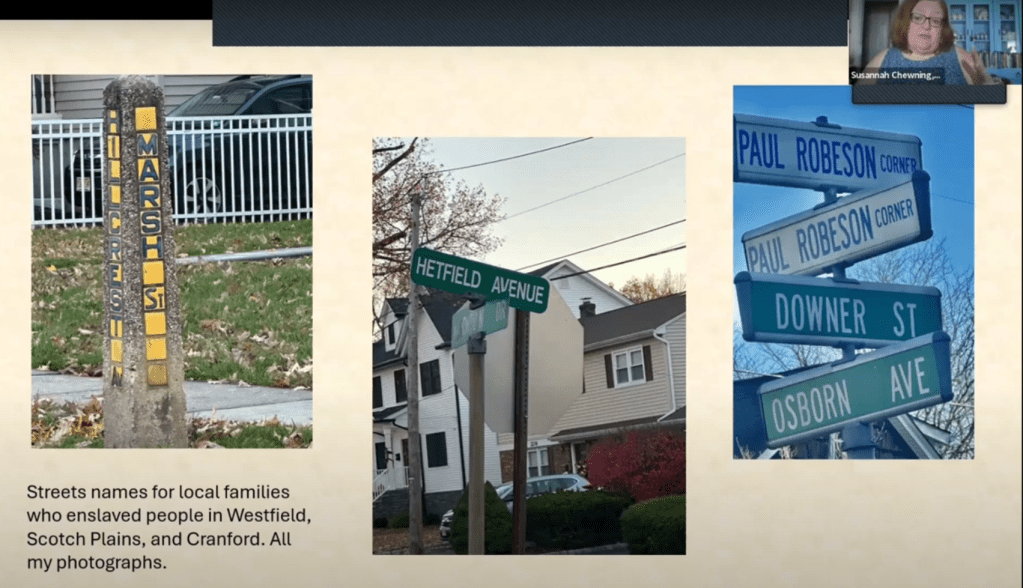

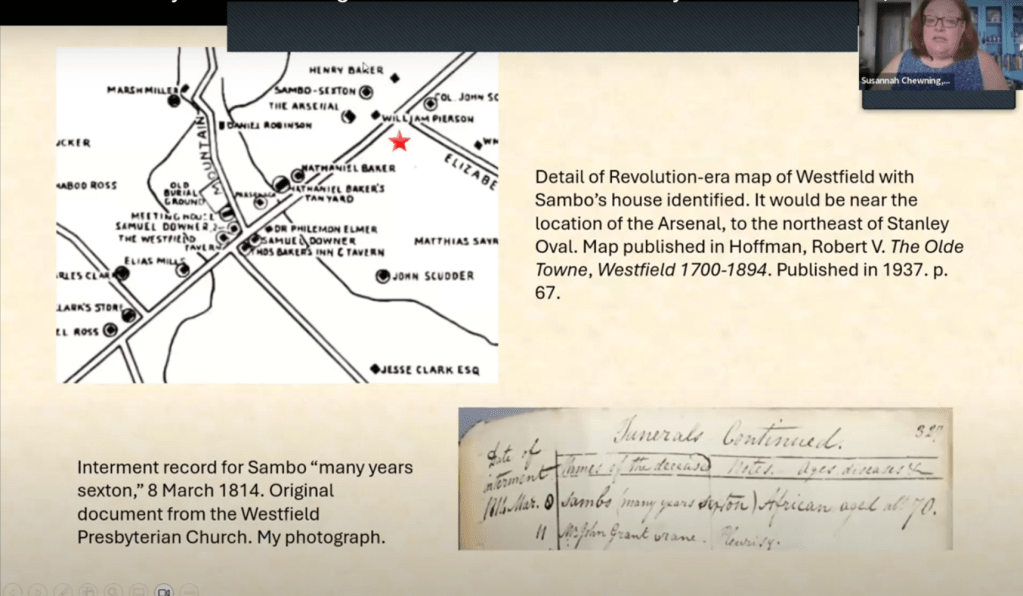

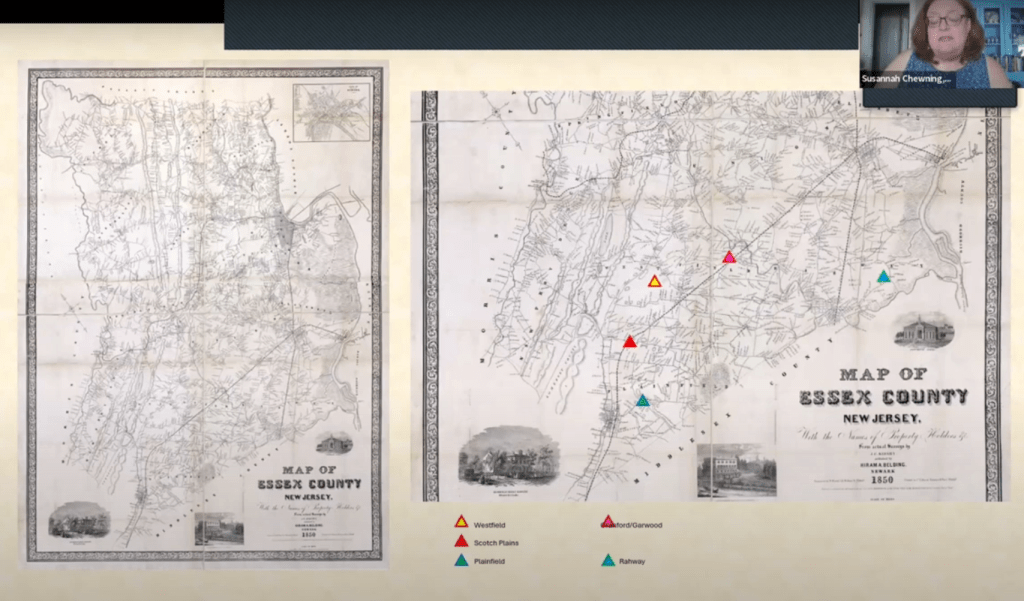

Dr. Chewning shared maps of what were historically known as the Westfields of Elizabethtown. She noted that many of the streets in present-day Westfield are named after influential early figures in the area. However, she also pointed out that many of these individuals were slave owners, a fact often overlooked in the local historical narrative.

Dr. Chewning then discussed the goals of her first grant-funded research project, conducted the previous year, before outlining the aims of the current project. These include building a comprehensive database documenting:

- The names of African Americans who lived in the region

- Burial locations of African Americans from the Revolutionary War era

- Possible descendants of those identified

Her database will also include information such as burial and interment dates, grave locations, personal stories, manumission and birth certificates, original documents, transcriptions, and links to related historical materials.

Dr. Chewning reported that her list of African Americans in the region has continued to grow, currently up to 200 individuals spanning from 1704 to 1866—the year slavery was finally abolished in New Jersey.

During her presentation, Dr. Chewning highlighted several individuals from her research, offering biographical details such as where they lived and what is known about their lives. By doing so, she brings voice and humanity to people who were often silenced by the historical record.

She also emphasized the wide array of sources used to construct these stories, including:

- Baptism, marriage, and death records from the Westfield Presbyterian Church

- Local tax and census documents

- Burial records from Fairview Cemetery

- Archives from the New Jersey Historical Society

- The New Jersey Slavery Records Database and Northeast Slavery Records Index

- Inventories of damages caused by British and American forces in New Jersey

- The Winans Collection at Princeton University

- Archives of the Westfield Historical Society

- Various books and local histories

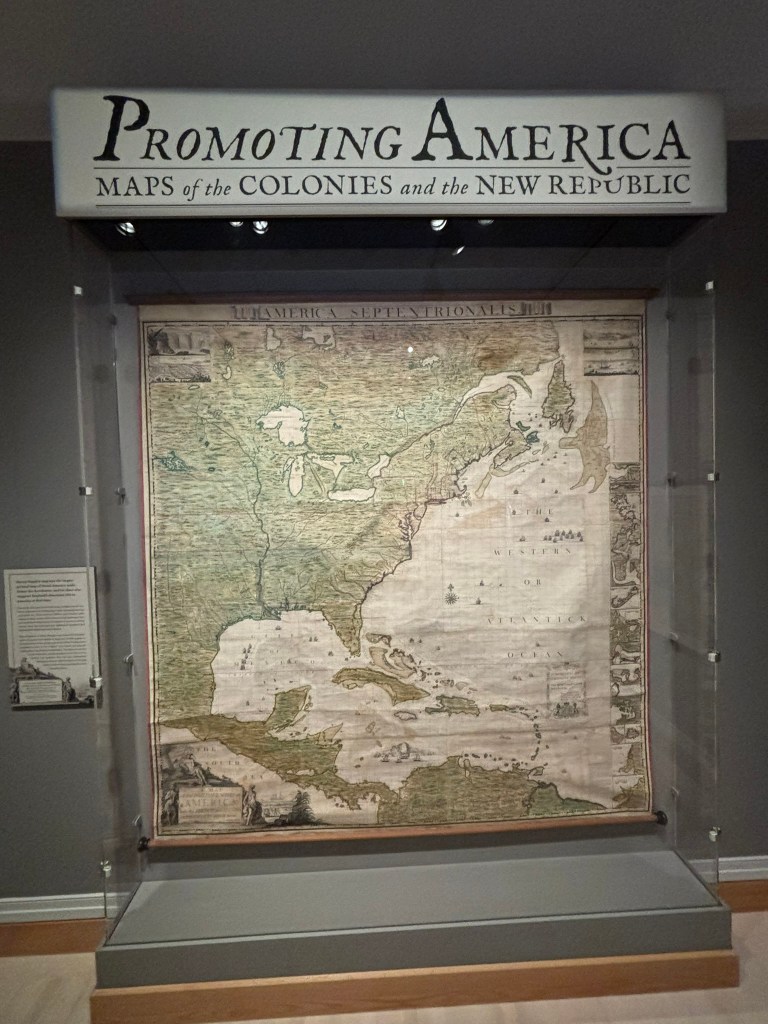

Dr. Chewning also addressed the history of slavery in Westfield by naming prominent early residents known to have enslaved individuals. She has a list of about seventy enslaved people living in the West Fields at the time of the March to Yorktown in 1781. She presented a range of primary sources that help tell their stories, such as sale records, damage claims, baptismal and burial records, Revolutionary War-era maps, runaway slave advertisements, and manumission documents.

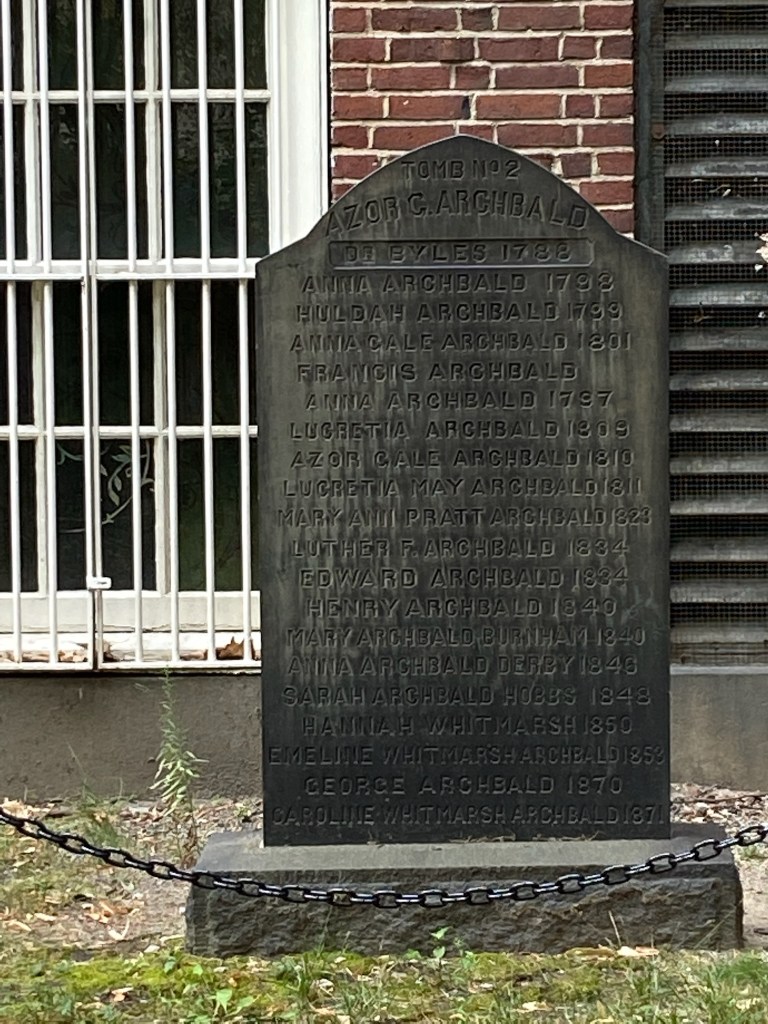

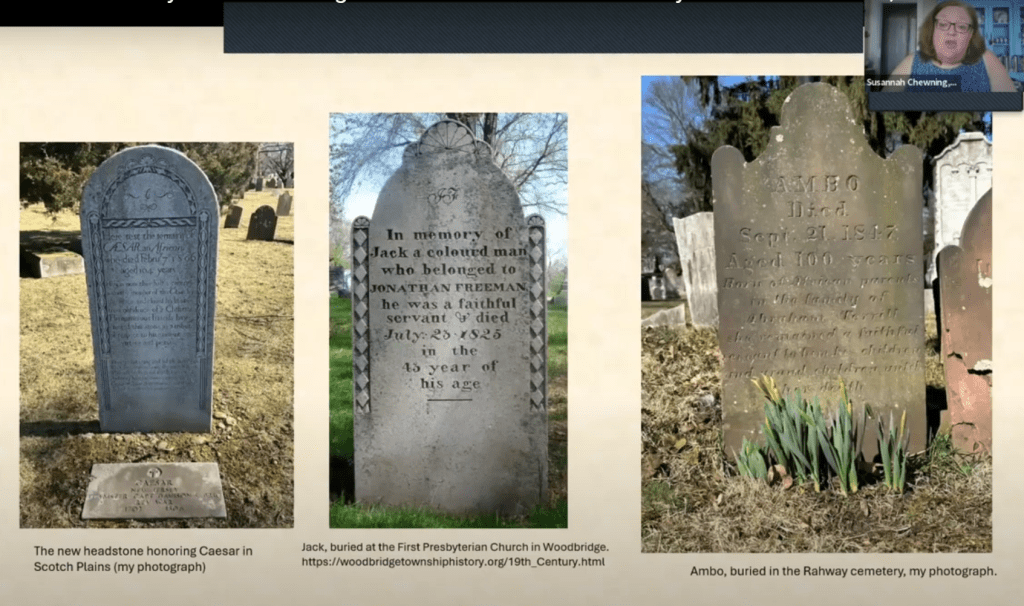

A key part of her ongoing work involves identifying burial sites of African Americans in the community. Dr. Chewning noted that enslaved individuals were known to be buried at the Old Burying Ground of the Westfield Presbyterian Church, the First Presbyterian Churches in Woodbridge and Elizabeth, as well as in family plots and home burials—many of which may have later been moved to Fairview Cemetery. She explained that further research is needed to match unnamed graves to individuals and that she is actively collaborating with Fairview Cemetery staff to advance this work.

Dr. Chewning shared photos of gravestones belonging to known African Americans in local cemeteries. She underscored that, to her knowledge, these are the only marked graves of enslaved individuals currently identified in Union County.

Dr. Chewning concluded her presentation by highlighting Wally Brown, a Westfield resident whose great-grandparents, Jack and Lembe Williams, are believed to be buried in the Old Burying Ground. Brown believes he knows the precise spot where they were laid to rest, though no marker currently exists. Dr. Chewning expressed her commitment to continuing this vital work.

My Presentation

Following Dr. Chewning’s presentation, I had the opportunity to discuss my blog with the audience. I shared how the blog started, the kinds of content it features, and how I became involved in the research project. It was a true honor not only to present my work, but to contribute to such a meaningful and collaborative effort. As mentioned earlier, you can watch the full presentation [HERE].

Building a Lasting Legacy

By shining a light on both prominent leaders and those whose names were nearly lost to history, this project reminds us of the power of local research to reshape our understanding of the past. As I discussed in Part 1, one of the aims of this research project is to create a lasting educational resource for the community. The team has been exploring and discussing the possibility of an enduring outdoor exhibit or monument that would allow the public to engage with this history in a meaningful way. The groundwork has been laid for this educational space that honors the notable figures who played an impactful role in Westfield and surrounding towns at the time of the American Revolution. Stay tuned to the Westfield Historical Society for updates on this future endeavor, and continue to check in with Benevento’s History Blog for future updates. Thanks for reading and supporting this project. Stay connected with the organizations listed below that have been involved with this project:

Check out these related posts: